37 Brunswick Square

37 Brunswick Square in 2024

What links a 16th century Venetian diplomat, Britain’s only Jewish Prime Minister, a Lloyd’s underwriter in a 19th century fraud case and a distressed cavalry officer in 1914? The answer is an elegant Regency town house in Hove known as 37 Brunswick Square.

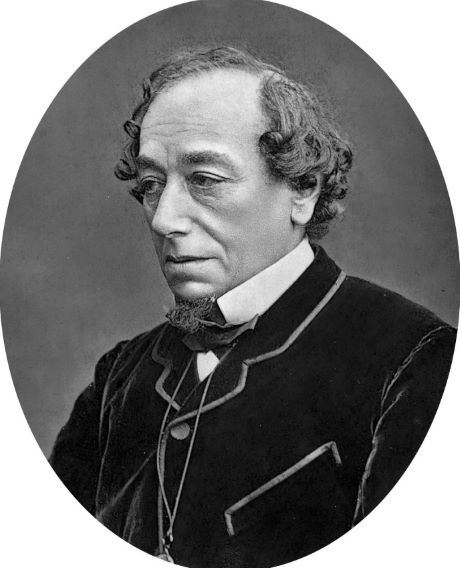

The first occupants of 37 (originally 35) Brunswick Square were George Basevi (1771 - 1851) and his wife Bathsheba (d.1850). George was a London merchant and one of the original Brunswick Town Commissioners, a magistrate and Deputy Lord Lieutenant of Sussex for 1844. He came from a prominent Jewish family and his sister Maria was the mother of Benjamin Disraeli, Britain’s first Jewish Prime Minister.

Benjamin Disraeli, George Basevi’s nephew

The family traced its origins back to merchants in the 16th century ghetto of Verona, then part of the Venetian Republic. One ancestor was Basa ben Sevi who in 1574 negotiated a peace treaty between the Venetian Republic, the Habsburg Empire and the Ottoman Empire. In gratitude he was granted coats of arms by all three states, a unique honour which has never been equalled. The resulting coat of arms featured a lion, an eagle and two crescent moons.

Another member of the family was Jacob Cervetto, great uncle of George and Maria. Born in Verona in 1690, he moved to London in 1739 and is credited with introducing the cello to England and teaching music to Frederick, Prince of Wales, the father of George III. He joined the Drury Lane Theatre Company as a cellist in 1744 and played alongside Charles Burney, father of the novelist Fanny Burney. He died in 1783 at his lodgings above a snuff shop in London.

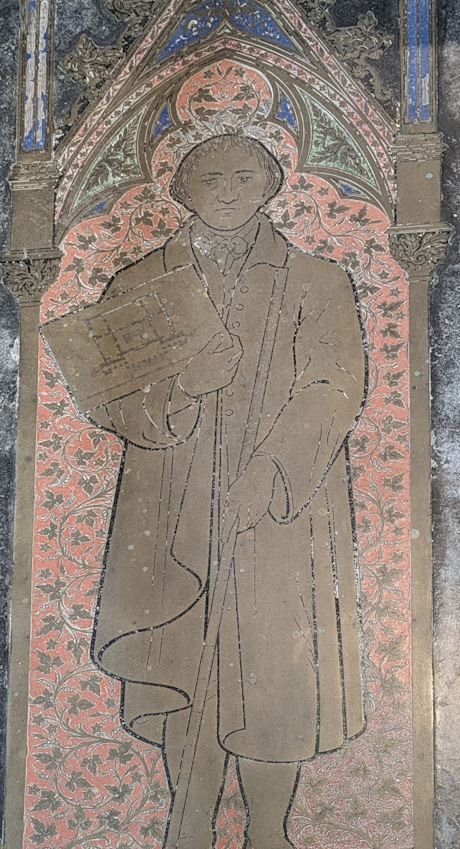

George and Bathsheba left Bevis Marks synagogue in 1817, at the same time as the Disraeli family, and converted to Anglican Christianity. They had three children: George Joshua (1794 - 1845), Nathaniel and Emma (d.1849). The younger George was a distinguished architect, who rebuilt Old St Andrew’s Church, where his father is buried, and built Belgrave Square in London and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. He was killed in a fall from Ely Cathedral when working there and is buried in the cathedral.

George Basevi’s tomb in Ely Cathedral

George, junior, is honoured by a blue plaque on his London home and his name appears on a Brighton bus. The younger George had two sons with his wife Frances (1810 - 1893): George Henry and James Palladio. George Henry was a colonel and engineer. James Palladio was also an engineer and military surveyor. He died in Kashmir in 1871, conducting a survey of the Himalayas.

George and Bathsheba must have been devastated by the deaths of two of their children and died within two months of each other, Bathsheba in December 1850 and George the following February. After their deaths, the house appears to have been unoccupied for most of the 1850s, barring a brief period when a John H Turner was in residence from 1852 - 1854. However, by 1859 it was once again a family home, occupied by the Bashford family.

Described simply as a landed property owner, William CL Bashford was born in Hampshire in 1818, his wife Frances in London in 1813. In 1861 their son Charles (b.1841 in Surrey) was away in the army, leaving his young wife Anne Argentina (b.1841 in Dorset) and newborn daughter Evelyne Argentina (b.1861 in Hove) with his parents. The Bashford’s daughter Frances Elizabeth (b.1840 in Fulham); younger son William (b.1844 in London); and Frances’s brother John Brome (b.1809 in Marylebone), also a landed property owner, completed the family. On census night a visitor is recorded, WFF Beacher Henare (b. 1844 in Hertfordshire), presumably a friend of the younger son. Three servants are recorded: Thomas Fashi, footman, (b.1829 in Brighton); Mary Wright, nurse (b. 1811 in Brighton) and Mary Kersey, cook (b. 1821 in Exeter).

By 1871 the younger William had moved out and was living in Brentford with his wife, Mary; he became a soldier like his brother. Frances Elizabeth has disappeared from the record, but her parents and uncle are still living in the house, along with Charles, his wife and three daughters. The number of servants has increased to seven, and their birthplaces include Derbyshire, Scotland and Shropshire.

Ten years later, the next census shows no trace of Frances’ brother John Brome or Charles and Anne’s middle daughter. William senior, now described as a magistrate and landowner, Frances, Charles and Anne are all there. William junior, now 37, has moved back in to the family home and has presumably been widowed and remarried. His wife’s name is given as Sophia and her age as 21. There are six servants living in the house. From 1888 the street directories list William senior and Colonel Charles Bashford as joint heads of the household. From 1891, only Charles appears. He and Anne were still there, with one live in servant, in 1901.

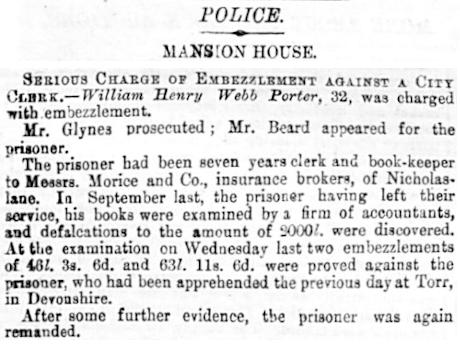

In the early 20th century, the house appears to have been empty for a few years, then in 1905 it is occupied by a widowed insurance broker named William Symondson (b.1837 in Edmonton, Middlesex). His father’s occupation is recorded variously as gentleman, merchant and insurance broker. William was a Lloyd’s underwriter and in 1867 he is mentioned in the Morning Herald in a case of embezzlement heard at the Mansion House in London by the Lord Mayor.

Morning Herald - 25 December 1867

The accused man William Porter, aged 32 and described as well dressed, had been a clerk and bookkeeper for Morice and Dixey, a firm of underwriters and insurance brokers, for seven years. In 1867 it was alleged that Porter had stolen £2000 (approx. £190,000 today) from his employer through a number of fraudulent transactions. A warrant was issued for his arrest and he absconded to Devon, where he was found and brought back to stand trial. William had given an open (uncrossed) cheque for £58 (approx. £5,500 today) to Porter for his employer. An uncrossed cheque, unlike a crossed one, could be cashed by someone other than the payee. Although William’s bank returned the cheque as paid, Morice and Dixey received only £10 (approx. £940 today). Porter denied the charge, claiming malice from his employer and was remanded in custody for a week. Frustratingly, the final outcome is unknown.

William is recorded at 37 Brunswick Square until 1915. The 1911 census shows that his sons William Herbert (b. 1866 in Croydon) and Ernest Leech (b.1877 in Croydon), who were both insurance brokers, lived with him, along with Ernest’s wife Margaret (b.1877 in Edinburgh) and son Eric (b. 1909 in Sevenoaks). The family employed six servants, born in Kent, Essex, Middlesex and Sussex.

From 1916 until her death in 1920, the house was occupied by an army officer’s widow, Judith Hughes-Onslow (1833 -1920) and her five servants. She had briefly lived at 41 Brunswick Square in 1911. Judith was born in Middlesex and in 1861 she married Henry John Hughes-Onslow (1816 - 1870). The couple had five sons, Arthur (b. 1862), Denzil (b. 1863), Constantine (b.1867), Julius (1870 - 1909) and the posthumous Henry Douglas (1871 - 1932), known as Douglas. Julius was a stock jobber and Douglas a solicitor. Constantine joined the navy in 1880 at the tender age of 13, presumably as a midshipman. He rose to become a Rear Admiral, married Evelyn Oxley in 1920 and died in 1948. Denzil joined the army and attained the rank of major. He was killed in action in France in 1916, leaving a widow Marion. He is buried in Meaulte military cemetery, France.

The oldest son Arthur was a man who loved horses and whose life was dominated by them. He was a major in a cavalry regiment and a talented amateur jockey. He served in the Boer War, taking his own horses out to South Africa.

Hussars in Colesberg, South Africa, 1900. Courtesy: National Army Museum

When war broke out in August 1914, Arthur and his horses were ordered to France, travelling on the SS Edinburgh. Arthur knew from experience how horses suffered in war and must have been overwhelmed by distress at putting his beloved animals through the ordeal ahead. He shot himself on board ship rather than take the horses into battle and is buried in Ste Marie cemetery, Le Havre. At a time when suicide was illegal and self-harm to avoid fighting was treated as desertion, Arthur’s death was handled with an unusual degree of consideration by the military authorities. The announcement of his death was deliberately timed to coincide with announcements about officers killed in a car crash and a plane crash, in an attempt to disguise the truth and spare his family from public opprobrium. No such delicacy was shown later in the war to the traumatized men shot for cowardice and their grieving families.

Research by Susan Wright (June 2024)

Return to Brunswick Square page