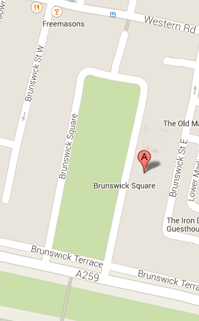

27 Brunswick Square

For nearly 200 years, 27 Brunswick Square has stood at the northern end of the square, facing downhill to the sea. During that time, it has sheltered a disgraced former Tory MP whose brother became a Liberal prime minister; an expert witness in a notorious poisoning trial; and a doctor who was so affected by the suffering he witnessed serving in the First World War that he became a passionate campaigner for peace.

Originally this house was listed in the street directory as a ‘furnished house’ and was let out to wealthy families who wanted a seaside holiday. Most of them are unknown but the census sheds occasional light. On census day 1851, the house was occupied by the Wigram family. The head of the household was Octavius Wigram, a brewer born in Walthamstow in 1795. He was accompanied by his wife Isabella (b.1794 in Dublin) and their daughters Isabella (b.1831 in Marylebone) and Clara (b.1834 in Walthamstow). The family was looked after by no fewer than seven servants: a lady’s maid, a cook, a housemaid, a kitchen maid, a nurse, a butler and a footman.

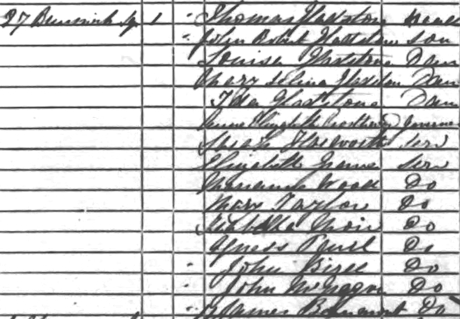

Ten years later, on the day of the 1861 census, the house was occupied by an even grander family, that of Sir Thomas Gladstone, baronet and older brother of the much more famous William Gladstone, who later became prime minister. Thomas, known as Tom, was born in Liverpool in 1804 and married Louisa Fellowes in 1835, inheriting the baronetcy in 1851 when his father died. Between 1831 and 1842 he had brief spells as a Tory MP in four different constituencies; his maiden speech in Parliament has been described as a ‘dim debut’, he campaigned to remove the tax on spirits, and was once unseated by a successful petition on corrupt electoral practices. He became disillusioned and left politics shortly after he was again accused by a fellow MP of bribery and electoral malpractice; these allegations were never proven. Unlike William, a Liberal, Tom was a lifelong Tory who irritated their father by his refusal to help with his brother’s election expenses. Tom devoted the rest of his life to managing his estates in Scotland and served as Lord Lieutenant of Kincardineshire from 1876 until his death in 1889.

27 Brunswick Square in the 1861 census

Tom and Louisa had one son and six daughters. Louisa (d.1901) and three of the daughters were not in Hove with the family for the 1861 census. The other three daughters Louisa (b.1838), Mary (b. 1842), Ida (b.1849) and son John (b.1853) were present, along with a governess, Grace Elizabeth Gladstone (b.1840 in Ireland), who may have been a poor relation. There were nine other servants: a cook, a lady’s maid, two housemaids, a kitchen maid, a school room maid, a butler, a footman and a page. Five of the nine were born in Scotland, where Tom owned an estate, suggesting that they at least were permanent members of the household rather than hired for the family’s stay in Sussex.

There was of course no census in 1862, nor is anyone listed as resident at Number 27 in any of the street directories for that year. However, the archives of the Royal Sussex County Hospital record the sad story of an 18-year-old footman Charles Bridger, employed at that address, who was admitted in November 1862 suffering from a fever with ulceration of the bowels. This was ‘fatal at an early period with symptoms of blood poisoning’. Charles is not listed on the 1861 census and nothing further is known about him.

Number 27 continued to be listed as a furnished house until 1876. It was then the home of a T. Johnson, Esquire until 1879, when the occupant is shown as Henry Wormald, Esquire. Nothing further is known about either of these men.

The 1881 census records two occupants. Elizabeth Court, a housemaid born in Somerset in 1845 is described as ‘Servant Head’ under Head of Household and the other name listed is that of Elizabeth Lambert, a kitchen maid born in Norfolk in 1862. Elizabeth Court also appears on the 1891 census, described as a servant of the Curling sisters, one of whom is head of household. The previous head listed in the directories was their brother Thomas Blizard Curling, a retired surgeon.

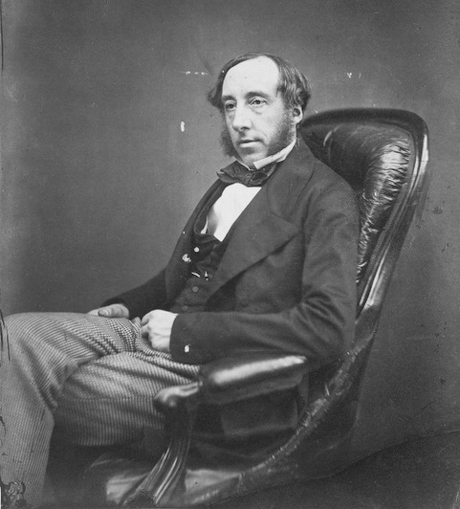

Thomas Blizard Curling FRS, Surgeon to the London Hospital

Thomas was born in London in 1811, the oldest child of civil servant Daniel Curling and his wife Elizabeth, née Blizard. They had a second son Henry (1815 – 1887) and twin daughters Emily and Louisa (b.1821). Elizabeth’s uncle Sir William Blizard was a surgeon and through his influence, Thomas became assistant surgeon at the Royal London Hospital in 1833, although he had no medical degree – not uncommon at that time before entry to the medical profession became regulated from the mid nineteenth century onwards. Younger brother Henry also became a surgeon. Medical degree or no, Thomas was clearly a brilliant young man. He won the Jacksonian prize in 1834 for his investigation into tetanus; this has been awarded annually since 1800 by the Royal College of Surgeons for a dissertation on a practical subject in surgery. He became a full surgeon at the Royal London in 1849; was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1850; and served as president of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1873.

Thomas was famous for his skill in treating diseases of the testes and rectum. In 1841 he published an article in The Lancet ‘Observation on the structure of the gubernaculum and on the descent of the testis in the foetus’ (the gubernaculum is gelatinous tissue which pulls the testis through the abdomen into the scrotum). This article was cited in the Journal of Paediatric Urology as recently as 2007. He also published a book on treating diseases of the testes in 1856, which went through several editions.

The Rugeley Poisoner, Dr William Palmer

Thomas was called on to give medical evidence in criminal cases at the Old Bailey. He features in five cases, usually as the surgeon who performed an autopsy or treated a victim. In 1856 he gave expert evidence on the symptoms of tetanus at one of the most notorious trials of the nineteenth century, that of William Palmer, the Rugeley poisoner. The writer Charles Dickens described Palmer as ‘the greatest villain that ever stood in the Old Bailey’. Palmer was convicted and publicly hanged.

Thomas married Frances Swayne in Wilton in 1839 when they were both 18. They had two sons, George (b.1846) and John (b.1849). Sadly he outlived his family; Frances died in 1878, John in 1884 and George on 22 February 1886, only days before Thomas himself died on 4 March 1886. It is to be hoped that he enjoyed his brief retirement in Brunswick Square.

After Thomas died, his unmarried twin sisters Emily and Louisa lived in the house. They appear in the 1891 census, described as ‘living on their own means’. They employed four female servants Ann Foster (b.1850 in Stoke Newington), Fanny Sutton (b. 1855 in Lewisham), Elizabeth Court, who was there in 1881, and Eva Warren (b.1874 in Brighton). The servants’ exact roles are not specified.

Like her older brother Thomas, Emily also appears as a witness in the Old Bailey records, in her case because she was unfortunately a victim of crime. At 6:30 pm on 7 November 1878, Emily was walking along Talbot Road in Marylebone when she was robbed of a muff holding her purse which contained £4 (almost £400 today). In her testimony to the court, we hear Emily’s own words: the man pounced on her, snatched her muff, hitting her on the chest in the process and ran off. Emily shouted, ‘stop thief!’ and gave chase; courageous behaviour from a 57- year- old woman, wearing a corset and long skirt, after dark on a November evening. Emily was fair as well as brave and made it clear to the court that the blow she suffered was part of the robbery and not designed to knock her down. The offender, William Stuchfield, an unemployed and homeless painter aged 24, was convicted of robbery with violence and sentenced to two years imprisonment.

Emily died later in the census year of 1891, aged 70. Louisa continued to live at 27 Brunswick Square and appears in the 1901 census, only months before her death that same year. Ann and Fanny still worked for her, described as cook and housemaid respectively. There were two other servants: Emma White, parlour maid (b.1863 in Oldham) and Charity Packham, kitchen maid (b. 1881 in Burgess Hill).

After Louisa’s death, the house passed to her nephew William Curling (1850 – 1894) and his second wife Amelia. William was the son of Henry Curling, brother of Thomas, Emily and Louisa. His first wife died in 1879, giving birth to their son William Graham Curling. In 1892, William married for the second time to Amelia Morison Gilmore, born in Thanet in 1866. They were married only two years before William’s death at the age of 44. Amelia continued to live in Brunswick Square. She was there on the night of the 1911 census, along with her married sister Ethel Hall (b. 1872 in Thanet) and her unmarried sister Jane Gilmore (b. 1873 in Thanet). Amelia employed three servants: Annie Avis, cook (b.1845 in Telscombe, Sussex); Sarah Grave, housemaid (b. 1828 in Brighton); and Leila Dyer, kitchen maid (b. 1897in Chelmsford). Amelia stayed in Brunswick Square until 1924; she died in Poole in 1937.

1924 was a year of change at 27 Brunswick Square. The house had new residents, Dr Douglas Crow and his wife Mary, and for the first time a phone number is listed in the street directory. Douglas Arthur Crow, known to family and friends as Tim, was born in Derbyshire in 1889. His father, Arthur, was a civil servant in the Inland Revenue and had married Coulsianna (sic) Peters in 1884. They had three children: Oxford (b. 1886 in Cambridge), Nora (b.1888 in Cambridge) and Tim. I can find no further trace of Oxford Crow. Nora became a doctor and died in 1969. The family moved around the country several times, and Tim attended schools in Loughborough, Hammersmith and Fort William. Tim studied medicine at Edinburgh University, winning two gold medals for academic excellence. He qualified in 1911 and took up a post as house surgeon at the Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital in Aylesbury.

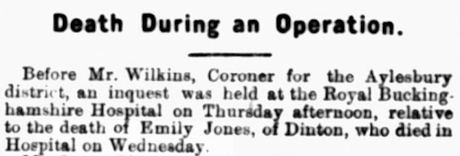

Buckinghamshire Advertiser and Aylesbury News 23 March 1912

In 1912 the Buckinghamshire Advertiser and Aylesbury News recorded that he acted as anaesthetist in an operation attempting to save a woman whose throat was so swollen she was struggling to breathe. Unfortunately, the anaesthetic used at the time was chloroform, which can also suppress respiration, and the patient died. The coroner stressed that the correct medical procedures had been followed and the verdict was death by misadventure.

In 1913 Tim married Mary Crabtree (1887 -1957) and at some time before 1916 they moved to Brighton, where Tim took up a post as an ear, nose and throat surgeon at the Royal Sussex County Hospital. He was still working there in February 1916, but joined the army later that year and was given a temporary commission as a lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). In 1917 he was promoted to the rank of captain. Tim was assigned to the 31st Field Ambulance Unit based in Salonika, Greece. He was horrified by the suffering he witnessed and the wastefulness of war and returned determined to fight for peace. In 2013, his granddaughter, the late Sally Dugan, wrote a blog about him called The Pacifist Faith of a Surgeon. She described him as a proselytising pacificist and member of the Peace Pledge Union, who published three books about his pacificist beliefs, as well as numerous articles.

Royal Sussex County Hospital - early 1900s. Source: Regency Society James Gray Collection

After the war, Tim returned to work at the Royal Sussex County Hospital. He and Mary moved to 27 Brunswick Square in 1924 and their daughter Gillian was born the same year. Like her father and aunt, she later became a doctor.

Tim was again a witness at an inquest in 1934, in a case which was widely reported in local and regional newspapers across the country. Six-year-old Eugenie Stacey, daughter of a Worthing hotel manager, had seven teeth removed. A molar slipped from the forceps and an X-ray showed that it was lodged in her lung. Tim was part of the medical team which tried to remove it from the child’s lung under general anaesthetic. They were unsuccessful and Eugenie died. The coroner recorded a verdict of death by misadventure.

Tim continued to work as an ear, nose and throat surgeon, to campaign for peace and to live in 27 Brunswick Square until 1945. He died by suicide in November 1945, injecting himself with a large dose of morphine at home. He was 56. Tim left a note for the coroner saying, ‘I cannot further endure this depression of spirit and have injected a large hypodermic of morphia’. The coroner’s verdict was that he had taken his life when the balance of his mind was disturbed, and he commented that Tim was ‘obviously overworked’. His granddaughter Sally Dugan disagreed. In her 2013 blog, she wrote that he had been dogged by depression since he was a young medic and she blamed this on his war time experiences, expressing the view that ‘it was the First World War, not the Second, which ultimately caused his death’.

Research by Susan Wright (August 2024)

Return to Brunswick Square page