7 Brunswick Square

An Incomplete House History

Researcher: David Jackson.

Writer’s Preface. This history is long, longer than anticipated, and so after an introduction, has been divided into 8 “Chapters”. The chapters are arranged chronologically although each one could be read separately. The focus in each chapter is on one particular resident or family: the longest is Chapter 3 but then the Halifax family occupied the house for the longest period of time. Chapter 7 is the raciest but Percy Courtenay may be the only resident who actually spent time in prison.

This history - like all histories - is a mix of fact and interpretation and where there may be some element of doubt about either the former or the latter, I have tried to acknowledge it.

Finally, about half the people who lived in this house (particularly in the 19th century) were servants. I have included many of their names and a few of their stories but most of this history is focussed on the lives of their masters and mistresses. Perhaps there is another history to be written.

Introduction

7 Brunswick Square is a four-storey building on the east side of Brunswick Square. Consecutive numbering in the Square begins in the South-East corner and so Number 7 is desirably close to the sea front. The construction of the house was completed by 1827 and it continued as one residence until 1938, when it was converted into flats. The building retains much of its original grandeur and is now Grade 1 Listed so it is astonishing to think that in 1945 Hove Council seriously considered its complete demolition along with the rest of Brunswick Square. Happily, that plan was scrapped and Number 7 survived intact.

Built in the 1820s, Number 7 was constructed following the strictly-applied methods and materials established in architect Charles Busby’s master plan for Brunswick Town. Also, it was designed with the presumption of the easy availability of servants. So, the basement consisted of service rooms: kitchen, scullery, wine cellar and perhaps a Housekeeper’s room. The ground floor was taken up principally with the Dining Room and the first floor the Drawing Room. The second floor contained the family bedrooms and the third floor housed the servants’ accommodation. The census of 1911 tells us that there were – by then - 11 rooms in the house (not including any scullery, landing, lobby or closet) and this number probably applied to the previous 80 years as well although plans were drawn up in 1882 for an additional two-attic-room extension on the back half of the house.

In his fascinating book “Fashionable Brighton”, Antony Dale opines that while Brunswick Terrace “abounded with well-known people”, Brunswick Square - with the exception of William Gladstone – had “hardly a single distinguished name to record”. This history will investigate who – distinguished or not – actually lived in just one of those houses. It will attempt to identify who actually lived in 7 Brunswick Square between the years of 1827 and the late 1930s.

The story begins in that post-Regency era when Brighton still enjoyed its reputation as the fashionable destination for the rich and celebrated. It continued through the entirety of the railway-connected Victorian era and into the 20th Century. It survived the horror of one World War and lingered up to the dark days immediately prior to the outbreak of another. It is time to open that front door and meet some of the people for whom this house was home.

Chapter 1. The Early Years

1830s & 1840s

“Mr Crockford”

All histories are incomplete and this history is particularly lacking in its early years, for the stark truth is that information about who then lived in the house is scant.

The building of the house was completed by the late 1820s. Its arrival on the market was advertised by a “TO BE SOLD” notice in the Brighton Gazette of 23rd February, 1829. It read: “7 Brunswick Square, Unfurnished. One of the Second Sized Mansions.”

Brunswick Square Today, Still - “One of the Second Sized Mansions”

Whilst acknowledging that it was not one of the largest in the Square, this short, unembellished advert seemed confident that the house would sell itself. Whoever bought the house seems not to have been the owner-occupier but a landlord who let it - perhaps furnished - to short term tenants.

This would explain why those tenants remain generally anonymous but one name has emerged from the shadows. 1830s Brighton was still the fashionable resort and the Brighton Gazette used to publish a regular column entitled “Fashionable Chronicle”. It was essentially a list of the arrivals and departures of the fashionable elite. Autumn was the main fashionable season and so on the 18th October (1832) the list of arrivals was particularly long. There was, also, a strict hierarchy of fashionableness. Way, way, down the list, long after the Lords and the Ladies, the Countesses, the Honourables, the Sirs, the Admirals, the Captains there was - in the second column of names - a ”Mr Crockford at 7 Brunswick Square.” So Mr Crockford is our first named resident and it is hoped that he enjoyed his stay in Autumnal Brighton.

Brunswick Square. early 1830s – We hope our Mr. Crockford enjoyed his autumnal stay

Further evidence that 7 Brunswick Square was let to tenants for much of the first 15 years of its existence is provided by another advert in the Brighton Gazette. This one came 12 years later, in May 1841.

It is interesting that the tone of this advert is different, a little more cajoling, a little more assertive suggesting that, perhaps, that the task of finding tenants had become just a little bit harder.

It was not until the mid-1840s that documentary evidence pointed to a more permanent residency in 7 Brunswick Square. We have a name and the name is Mr. Paul Malin. One of the Brighton directories confirmed that “Paul Malin Esq.” was resident at 7 Brunswick Square in 1845 and three years later, in 1848, it was listed as the home of “Mrs Paul Malin”.

So, what do we know about the Malins? Sadly, Paul Malin did not live in the house for very long as the Gazette informs us that he died in his Brunswick Square residence on the 28th July, 1845. He was 70. He was a Sussex man, born and baptised in Frant, a village in East Sussex, just a few miles from Tunbridge Wells. A few years earlier, in 1841 he was living in Regency Square, Brighton with his wife Mary Anne then aged 50. At around the same time their daughter – also named Mary Anne – married Alexander Farquar, a clergyman’s son from Aberdeenshire. The wedding (on 6th January 1842) was held at St. George’s, Hanover Square, in London.

Putting this information together: the fact that their daughter was married in a fashionable Mayfair church – arguably the fashionable London church – and that their addresses in the 1840s were two of the more expensively fashionable Brighton Squares leads to the supposition that the Malins were at least comfortably off. The only clue that Paul gives about his “occupation” is that he was of “independent” means.

After Paul’s death Mary Anne continued to live in the house for another three or four years but eventually moved up to Aberdeenshire. We are told that Mary Anne – in the wonderfully archaic language of the time - “relict of the late Paul Malin” once of Brunswick Square died in Muiresk House, Aberdeenshire in July 1872. She was 81.

Muiresk House was - and still is - a beautiful 17th Century Country House on the banks of the River Deveron in North East Aberdeenshire. So, Mary Anne Malin seems to have had the good fortune to have spent most of the last thirty years of her life living in not one but two elegant houses.

An interesting if random fact about Paul and Mary’s marriage is that there was quite a large difference in their ages: Paul was 17 years older than Mary and when they were married at All Hallows Church in London on 5th November, 1807 (“Bonfire Night”), Paul was 33 and Mary Anne (nee Smith) was just 16. Perhaps eyebrows would be raised now; perhaps eyebrows were then.

Chapter 2. The Oldfields

1851

A Mystery Explained

Who was living in 7 Brunswick Square on the 30th March, 1851? This question can be answered with certainty albeit certainty tinged with a degree of mystery. The 30th March was a Sunday and living in the house that evening was Mrs Letitia (sometimes she used the spelling Laetitia) Oldfield.

Letitia, born in Shropshire, was 48 years old and described herself as a “Fund Holder”. She was living in the house with her 17-year-old unmarried daughter also named Letitia - Letitia Anne to be precise. There is no mention of a husband and it was in fact an all-female household as the two members of the Oldfield family were looked after by three female live-in servants: a Cook, Elizabeth Alsop, a Lady’s Maid, Sarah Champling and a House Maid, Sarah Hollick.

The number of servants in a Victorian household can tell us a great deal about the wealth and status of the family. So, what do we know about the Oldfields and their immediate neighbourhood?

Number 8 – next door to the North - was listed as “uninhabited” but Number 9 was probably a little less quiet as it housed Mr Mortimer Ricardo (a “Landed Proprietor”), his wife and their 6 young children aged between just a few weeks and 13. It was quite a large family and supported by quite a large retinue of servants. There was a Governess and a Tutor and 4 other live-in servants.

Next to them in Number 10 was the Hankey family (well known to RTH visitors). Retired Merchant, Mr Thomson Hankey, was a former employee and “annuitant” of the East India Company and with his wife Martha had been living in the house for many years. In 1851 they were there with their grown-up daughter - also named Martha - youngest son Beaumont, daughter-in-law, Catherine and 2-year-old grandson, Wentworth, (the Hankey family seemed to have a taste for rather grand first names). This extended family of 6 was supported by a staff of 9 live-in servants.

Letitia’s neighbour to the South at Number 6 was a widow, 44-year-old Eliza Tewart. Eliza also described herself as an “annuitant” and the annuity must have been quite considerable as it was sufficient to support her 7 children (6 girls and one boy ranging in age from 6 to 18), a Governess, a Housekeeper, a Cook, three Maids and a 17-year-old Page.

There is a revealing general statistic from 1851 that almost exactly half the inhabitants of Brunswick Square were (live-in) servants. This little neighbourhood of the 4 or 5 houses around Number 7 does seem to support that vital statistic. The other tentative generalisation to be made is that most of these houses at that time seem to be occupied by affluent middle-class families living primarily on investments, annuities and pensions.

However, our focus is on Number 7 and so back to the “mystery”. Why is there no mention of a “Mr Oldfield”. Where is “Mr Oldfield”? What are the possibilities? He may, of course, have died but the census convention was that Letitia would then describe herself as “widow” - she doesn’t. He could have divorced her - vanishingly rare in the mid-Victorian period. He could simply have been away elsewhere on the day in question (census rules only recorded those who actually slept in the house that particular night). In fact, it was none of the above. Henry Swann Oldfield - Letitia’s husband of almost 30 years - was in Bengal.

Brunswick Square, East Side, early 1850s: very suitable accommodation for the family of a Senior Officer of the East India Company, home on “Furlough”

Henry Swann Oldfield was a lifetime employee of The Honourable East India Company. He was born in Fort William - not the Scottish town - but the immense fort built by the British on the banks of the Hoogly River near Calcutta. He married Letitia in Meerut (in what is now Uttar Pradesh) but back then in the HEIC’s “Bengal Presidency”. The East India Company – backed up by its private army – managed the customs, taxes and judicial systems in Bengal until 1868. Then, following the Indian Mutiny, the British Crown took over in what was to become the start of the British Raj. Henry had a succession of increasingly important positions within the Company.

As a young man in 1824 he was promoted to be “Head Assistant” (essentially a clerk). In the 1830s he was (tax) “Collector of Calcutta and the 24 pergunnahs”. (a pergunnah was the Hindustani word for a small district, part of a zillah). By the 1840s he was “opium agent and superintendent of salt chokeys (sic) in Bihar”. He ended up as a “Civil and Sessions Judge in Midnapore” (now Rajasthan) then West Bengal. The Indian connection was continued by one of Henry and Letitia’s sons: Henry Thomas Oldfield. H.T. had a highly successful military career - first in the Company’s Bengal Army and latterly in the 6th Bengal Lancers. He finally retired in 1882 having reached the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

Many years later in 1872 a - by then - retired Henry Swann and Letitia were living in one of the smarter parts of London, Oxford Square, near Hyde Park and in 1876, Letitia died and, in an obituary, she is described as “the dearly loved wife” of Henry Swann Oldfield “late of the Bengal Civil Service”. That reference suggests that Henry had continued to work for the British Crown after the dissolution of the HEIC in 1858.

Henry Swann Oldfield was one of the many, many Victorian “British in India”. He was born in India; two of his three children were born there and he spent his entire working life there. Company Officials and their families had regular “furloughs” back in Britain and sometimes there was a lengthy, mid-career furlough of up to two years. This is probably what brought the Oldfield family to Brighton although there is no direct evidence that Henry himself spent time in the house during Letitia and Letitia Anne’s two-year residence there. Henry may have been conspicuous by his physical absence but he and India would have been constantly in his family’s thoughts and his substantial salary paid their bills. Henry finally died in Westminster on the 4th May, 1887. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery. His daughter, Letitia Anne – still in her teens during their time in Brunswick Square – was, eleven years later, to marry a clergyman. Her husband was Rev. Thomas Fardell, son of the Canon of Ely Cathedral and in his will, Henry Oldfield left his estate to the Rev. Thomas and Mrs Letitia Fardell.

Henry Oldfield’s East India Company salary paid the bills.

The Oldfields, mother and daughter, only lived in the house for a short period but we have some impression of the interior of the house they lived in and how it was furnished. For, shortly after their departure, in December 1852 the entire contents of the house were auctioned off by Messrs Bartholomew & Co. They listed all the items for sale.

“The whole of the modern & elegant household furniture and effects from the premises of 7 Brunswick Square [are to be sold]. Carpets and Damask Curtains from the Drawing Room. Chairs and Sideboards from the Dining and Breakfast Rooms. Mahogany four post beds with Damask Hangings, bedding and pillows from the bedrooms.”

Mahogany and Damask do seem to feature quite prominently. The house was clearly being emptied and perhaps the furniture was being sold by the Oldfields prior to their return to India but more likely it was being sold by the Landlord prior to a sale of the house.

For the next 20 years the House was occupied by the members of one family. Let us call them the Halifax family.

Chapter 3. The Halifax Family

Aristocracy?

C1853 – C1873

They lived in the house for about twenty years but they were not - in the conventional sense - a family.

Let us start with some facts. The Brighton Directories tell us that from 1854 onwards, the residents of 7 Brunswick Square included “Lady Halifax” and “The Misses Halifax” and their residency in the house was confirmed by the Census of 1861. On April 7th of that year, Elizabeth Paul, widow, is listed as being Head of House along with her unmarried sisters: Gertrude Halifax and Caroline Halifax. They were living in the house along with their Butler, Richard Bradley, their Cook, Eliza Shilton, two “Lady’s Maids”, Ann Hellan and Sarah Chapman and two Housemaids, Eliza Burton and Elizabeth Brendon. The Halifax sisters were clearly people of substance.

Sometimes, however, we have to be cautious about “facts”. That 1861 Census lists the sisters’ ages as Elizabeth “60”, Gertrude “54” and Caroline “65”. All three ages are, in fact, verifiably untrue. All three sisters were born back in the later years of the 18th century (their father died in 1790) and their actual ages (in 1861) are: Elizabeth 76, Gertrude 84 and Caroline 77. What can have happened? Perhaps a clerical error, perhaps the Census Enumerator made a mistake, perhaps it was a sisterly joke. We shall never know but of the three guesses, the third is the most attractive!

What do we know about the earlier lives of these three elderly sisters? There are two significant features. They came from a highly talented, well known and successful family but their link with aristocracy was tenuous and there was no “Lady Halifax”.

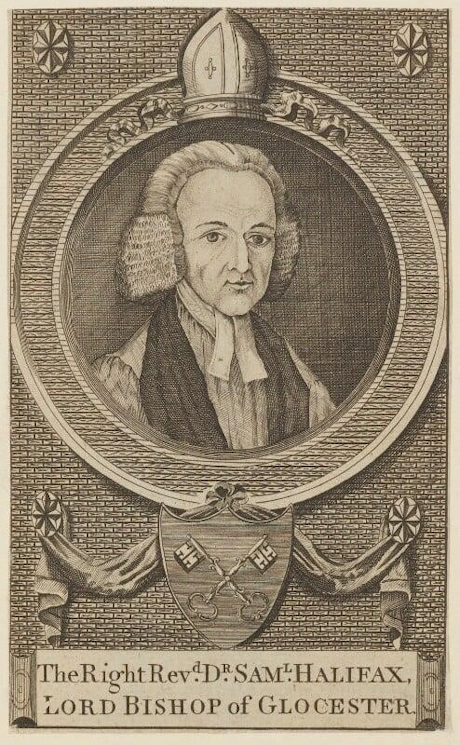

Their father, Samuel Halifax, actually came from quite a humble background. He was born in 1733 - the son of a Mansfield Apothecary - and he was a brilliantly intelligent man who became both senior Churchman and Academic. At various times he was: Professor of Civil Law at Cambridge, Lord Bishop of Gloucester and - before his premature death from kidney stones in 1790 - Bishop of St. Asaph in North Wales. He was, apparently, the first Bishop to serve in both England and Wales.

Samuel Halifax – the sisters’ distinguished father

He and his wife Catherine had six daughters: Gertrude, Charlotte, Marianne, Caroline, Catherine and Elizabeth. Their uncle - Samuel’s younger brother - Thomas Hallifax (the name was sometimes spelt with a double l), also had a highly successful career eventually becoming Senior Physician to George 4th. This connection may well have had a bearing on the girls’ (his nieces) future lives.

All 6 of the girls were the recipients of a Court Pension. Court Pensions then were part of the so called “Civil List”. It was a matter of much contention as these pensions were granted by the sovereign but paid for by the State. Each of the six Halifax sisters received £48-15s pa (worth perhaps something like £10,000 in today’s money).

The beneficiaries and the amount they were paid were published regularly in many newspapers and they were hugely unpopular. Many newspapers launched angry even vicious campaigns against this – as they saw it – corrupt system. Although the names of the beneficiaries and the amount they were paid was in the public domain there was no obligation on the Crown to explain why the payment had been made. This lack of transparency led to widely held suspicions that they were pay offs for favours or bribes.

English Radical, William Cobbett, named and shamed the sisters

Radical reformer, William Cobbett, writer and publisher of his “two-penny” pamphlet actually named and shamed the six sisters in one edition; “a pretty little snug covey” he described them. Other papers were even more forthright about allegedly undeserving recipients: “Sir Wm Johnston Bart £714. An old bachelor of great property spends all his time in Bath and other watering places being altogether an absentee”. Rev Kuper “Must be a German, probably a Hanoverian. What claim can he have on the taxes of England?” And Dame Isabella Congreve who in her younger years was “much about the person of George 4th” (ahem!)

The public fury about these Civil List Pensions might seem excessive to us but was perhaps analogous with our more contemporary anger about the suspected misuse of taxpayers’ money. It is not clear why the six sisters continued to receive their pensions but one rumour was that George 3rd originally granted it to their mother, Catherine, when she was prematurely widowed in 1790. The other more damaging gossip was that it was arranged by the venal George 4th after lobbying from his physician (and the girls’ uncle) Thomas Hallifax. George 4th, formerly the Prince Regent and something of a hypochondriac, was very adept at spending other people’s money and maybe just grateful for staying alive.

Elizabeth Paul was not the eldest sister but she was referred to as “Head” of the household in 1861 perhaps implying that she owned the house. Seventeen years earlier in 1844 she had married Sir John Dean Paul (Bart), landowner, banker, painter and author. He had been created 1st Baronet of Rodborough (in Gloucs) by George 4th in 1821 thus reviving an extinct title. Elizabeth was Sir John’s third wife and at the time of their marriage was in her late 50s - Sir John was in his late 60s. Needless to say there were no children although Sir John did have a son and heir by his first wife who, when Sir John died in 1852, became the 2nd Baronet Rodborough. A Baronet is not a Lord but according to official etiquette a baronet’s wife is entitled to be called “Lady”. So, Elizabeth was indeed Lady Paul (but never “Lady Halifax”). When Sir John’s son eventually married, Elizabeth’s correct title became the Dowager Lady Paul.

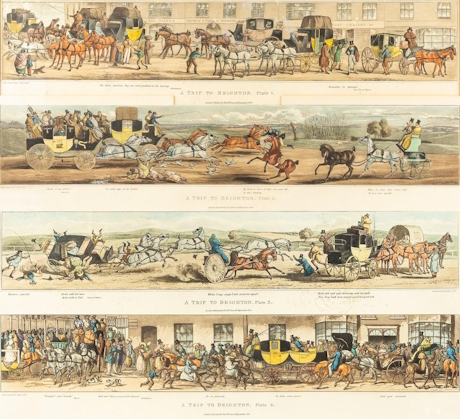

It was sometime after her husband’s death that Elizabeth linked up with her two unmarried sisters and their life at 7 Brunswick Square began. Sir John had been, amongst other attributes, a prolific painter. He was particularly fond of painting horses and it is certain that at least some of those paintings were bequeathed to his last wife. So, it is more than likely (and very agreeable) to think that several of those paintings were to be seen hanging on the walls at 7 Brunswick Square. (See below).

During her time in the house Lady Paul had to deal – quite unfairly – with the stigma attached to her late husband’s son by his first marriage. In 1855 Sir John Dean Paul (junior) the 2nd Baronet was convicted of fraud. It was the most sensational case that gathered headlines for months. It involved the previously respected and respectable banking house: Strahan, Paul & Bates. Hundreds of thousands of pounds went missing from the accounts of (amongst many others) Lord Palmerston, The Duke of Rutland and numerous religious and charitable institutions. The 2nd Baronet was held to be the ring leader and very much a modern robber baron. He was charged, convicted and sentenced to 14 years. The Dowager Lady Elizabeth Paul was in no way involved in the crime but her name was contaminated by association. Despite this embarrassment, Lady Paul lived on until her death at 7 Brunswick Square on the 18th May, 1869. Her passing was widely reported in the newspapers.

What can we say about her two unmarried sisters – Gertrude and Caroline? Well, they remained unmarried and seem to have spent much of their lives living together. So, for example, back in 1851 they were sharing a house in Bedford Square, Brighton and 20 years later on 2nd April 1871 they were still living together at 7 Brunswick Square. Gertrude had, by then, assumed the mantle “Head of House” and she was there with Caroline now 87. A third (previously married) sister had joined them. She gave her name as “Luckie” (perhaps a nickname or misprint) with the surname Ricketts and her 60-year-old daughter was also living in the house. Each of the three sisters described themselves as “gentlewoman”. And - just as in 1861- they had six servants to care and cater for them although after ten years the personnel had changed entirely - apart from just the one survivor: Sarah Chapman, Lady’s Maid, was still in service.

A few years before this, the Brighton Guardian reported on a troubling incident experienced by the sisters at 7 Brunswick Square. It happened on the 28th August 1867 and it involved William Yates Gillespie. He was “Butler in the service of the Misses Halifax”.

The previous day he had been given £6 (a £5 note and a sovereign) by Caroline Halifax to settle various bills owed to local trades people. Gillespie, instead of paying the bills, went to a public house in nearby Lower Market Street where he changed the £5 note. He then went to a beer shop in Cross Street where he drank ale followed by several visits to other local beer shops. Later having returned home “much the worse for drink” the Cook asked him if he had paid the butcher for the suet. He replied “No” and that he had lost the money. When she learned what had happened, Miss Caroline (she was in her 80s) ordered him to leave the house. He refused and demanded back pay of £1-6s-8d. He was told in no uncertain terms that as he had already received an advance payment of £2, he should leave forthwith. Mr. George Breach, the Police Superintendent, was summoned and Gillespie was arrested and placed in custody pending his appearance the following Monday before the Hove County Bench. It is unclear what the outcome of that hearing was but, suffice to say, by 1871 Gillespie was no longer the butler. He had been replaced by a Belgian with the delightful name of Napoleon Drigcott.

Another snippet of news from the Brighton Guardian gives us, perhaps, a clue about Caroline Halifax. The Brighton & Hove Soup Relief Fund was a local charity active in the 1860s dispensing - as its name suggested - much needed sustenance to the poor and needy. Three times during a particularly cold January week, the charity distributed “8,921 quarts of nutritious soup”. Its very existence reminds us of the great disparities of wealth in mid-Victorian Brighton. Caroline was a contributor so, for example, when a collection was made at Hove Library, she donated 10 shillings to the fund. Does this suggest that we should see her as a woman of conscience and compassion? 10 shillings was a substantial sum (although Lady Hussey and Rev. Tomlinson both donated £1) but then Capt. Forster and Lady Onslow only gave 5 shillings. It is difficult to make judgments. Also, the donors probably knew that their names would be listed in the local newspapers so cynical modern observers might dismiss the whole process as virtue signalling by the comfortably off.

Samuel Halifax may have died prematurely but his daughters were truly remarkable for their longevity. Gertrude lived to be 95 and Caroline died in March 1873 at the age of 89 and - shortly after this - the Halifax sisters’ long residency at 7 Brunswick Square came to an end.

There was however a post script. Following Caroline’s death, the contents of the house were auctioned and the list of items gives a fascinating glimpse into what the inside of the Halifax house looked like.

The auction of 20 years earlier had consisted mainly of solid, sensible Victorian furniture and furnishings. This one was different. The Auctioneers, Crouch & Stevens announced that they had been “favoured with instructions from the executors of the late Miss Halifax”. There was much “valuable old porcelain” – Derby, Worcester and Dresden. There was “a library of over a thousand volumes” including works by Dante, Homer, Plutarch and Shakespeare and also by more “modern” writers like Dickens and Captain Marryatt. There was much elegant furniture. Then there were water colours and paintings by highly respected artists like the 17th century baroque painter, Francesco Albano, and the 18th century portraitist, Jonathon Richardson. Finally, there were a “number of original paintings and drawings by the late Sir John Paul, Bart.”

Did some of those paintings adorn the walls of the Drawing Room and Dining Room at 7 Brunswick Square? Of course they did!

John Dean Paul’s Set of 4 Brighton Pictures.

Did these adorn the walls at number 7?

Chapter 4. Mr James Martin & Family

Trade

C1879 – C1883

No-one lived longer in the House than the Halifax sisters and by contrast the Martin family’s stay was brief. There were other contrasts. The Halifax sisters had connections (however tenuous) with aristocracy even royalty; the Martins were trade.

They were an elderly couple by the time they arrived in the house. James Martin was 79 (in 1881) and his wife Betsy (sometimes referred to as Bessie) was 65. They were living in the house with a granddaughter, Mary Anne, who was in her 20s and they were looked after by just two domestic servants – quite a low number by the standards of the time. Their neighbours in 6 Brunswick Square, for example, employed 4 servants and at Number 8, it was 5 including a Butler and a Cook.

They were not born in Brighton – both James and Betsy were born just across the county boundary in Portsea Island, Hampshire – but that apart they were Brighton through and through. They spent their entire adult lives in Brighton and their lives were inextricably bound up with the development of the town. James, born in 1801, lived until 1890 so his life stretched for almost the entirety of the 19th century and it would not be too much of an exaggeration to regard him as the archetypal “Mr. Victorian Brighton”.

At the time he was living in 7 Brunswick Square, James described himself as living on “Income House Property Dividends” suggesting that he had, in later life, invested in property but he was in fact a retired Upholsterer. He had for many years run a thriving and successful Upholstery Business in East Street Brighton. “Martin’s General Furnishing Upholsterer” was located at 59 East Street on a site that was “Adjoining Hanningtons”. That latter phrase – used frequently in advertisements - was, presumably, designed to suggest some association with the department store. Hanningtons (the so called “Harrods of Brighton”) was for almost 200 years the town’s most prestigious store.

59 East Street today

James' three sons worked in the upholstery business and it was clearly a substantial operation, employing (in 1851, for example) 13 men and 2 women. A decade or so later we get some impression of the scale of their premises when, in 1862, they were put up for sale. The business was by then known as “Messrs James Martin & Sons – Extensive Upholsterers”.

The advertisement speaks of “splendid premises”, “built without regard for expense”, “imposing elevation”, “commanding frontage”, “access to Old Steine”, “suitable for bank or insurance house” etc. Those East Street premises are made to sound mighty impressive.

James Martin was not just a man of business. After selling the business (and indeed before) he was prominent, very prominent in Brighton public life. To recognise the unique contribution that James Martin made, we need to know a little about how local government in Brighton was transformed in the 19th century. From the late 18th century onwards, Brighton had been run by an unelected group of “Commissioners” but there was increasing pressure in the first half of the 19th century for more democratic governance.

This was eventually achieved with “incorporation” in 1854 when Brighton became a Municipal Borough. There were 6 Wards each with 6 elected Councillors usually referred to as “councillmen” (they were of course all men!) and in 1873 Preston Ward became the 7th Ward. James Martin straddled both systems serving initially as one of the Commissioners in the early years and later elected as one of the 6 Councillors in Preston Ward. Newspaper reports suggest that he was active in many of the debates and decisions affecting Brighton’s development including the acquisition of The Royal Pavilion from Queen Victoria, the construction of the West Pier and frequent contributions on the management of schools and the Brighton Workhouse.

James Martin was an energetic participant in 19th century local government but what can we glean about his more general political beliefs and affiliations? Perhaps a clue emerges from the Brighton By-election of July 1860 - following the death of the sitting MP. James Martin was part of the small “Securing Committee” supporting the candidacy of Mr Frederick Goldsmid. Goldsmid was standing under the banner of the newly formed Liberal Party - generally seen as a “progressive” party. So, this might suggest that James was himself someone sympathetic to progressive ideas but equally we should perhaps be cautious about attaching too much significance to this as he was, in at least one other way, very much a figure from a past age.

James Martin was the very last “High Constable of the Whalebone Hundred”. The very name is redolent of ancient Brighton history. The “Whalebone Hundred” was the old name for the area roughly synonymous with the Parish of Brighton. (Whalebone is probably a corruption of Wellesbourne – that lost river that used to flow under the Old Steine). The Constable’s many tasks included bringing miscreants before the law courts but by the time of James’ appointment the Office was entirely ceremonial. He would wear 18th century dress and represent Brighton at fetes, banquets and so on.

Does this appointment suggest that James Martin was seen as a conservative figure, more wedded to a romanticised past than the present? Perhaps or perhaps not for when Brighton was finally incorporated in 1855, James realised that it was time for this ancient Office to be abolished. He organised a ceremonial meeting where he presented his badge of office and silver staff to the, by then, Mayor of Brighton. This sounds like the action of a man who has decided that the time had come to accept the new democratic reality. Anyway - we are told - that subsequently the Mayor passed the silver staff to the Brighton Museum for safekeeping. Perhaps it is still there or perhaps it is this staff pictured below, that the Museum returned to Brighton & Hove City Council in 2023. See Note 1 - at the end.

Is this what was once the Constable’s Silver Staff now kept at Brighton City Hall?

The Martins’ time in Brunswick Square was relatively short but not without tragedy as two of their sons died early in their 20s and 30s although James’ eldest son and namesake, James Martin (jnr), continued the family tradition of public service. After 7 Brunswick Square, James and Betsy moved to nearby 17 Brunswick Place and it was there in 1890, that James died. He was buried in the family vault in the Extra Mural Cemetery.

Chapter 5. The Stehn Family

Migrant Success Story

1880s & 1890s

Not long after the departure of the Martins in the early 1880s, Mr Christian Stehn and his family moved in. At that time, Christian Stehn was a corn merchant or as he termed it a “Corn Factor” although just a few years later in 1891 he was to describe himself “Retired Merchant”. As his name might suggest, Christian Stehn was born in Germany (Hamburg, probably) back in 1818 and it was some 60 years later that he moved into the house with his English wife Susan and their, by then, four grown up children.

Many years earlier, as a single young man, Christian had emigrated and settled in London. His Corn Merchant business – “Christian Stehn & Co.” was located at 134 Fenchurch Street and the business prospered. Christian seemed to be of an anglophile disposition as he applied for and became a “naturalised British subject”. He seemed proud of this fact and often included it in official documents. At this time, he was living in Lewisham in South East London and in July 1853 he married a local girl, Susan (nee Douglas). The wedding was held at All Saints Church in Norwood. Christian, by then, was financially secure and had reached the midway age of 35; Susan was 20. The children were all born in Sydenham: Charles Christian (born in 1855), George (1859), Arthur (1861) and Ellen (1864).

As mentioned, the business had prospered and by the time the Stehns moved to Brighton, they were an affluent family living first of all in Kings Road and later moving to 7 Brunswick Square. By this time London and Brighton were well connected by railway and as, initially, all of the men: Christian, Charles, George and Arthur were still working in London they would have been part of that early generation of Victorian train commuters. During their time at the House, they never had less than four servants: usually a Cook and various maids.

However, in other ways their lives were blighted by a series of what must have been extremely painful family tragedies. The tragedies affected three generations of Stehns. Just a few years after the family moved into 7 Brunswick Square - on the 10th May, 1887 - Susan Stehn died. The cause of death is not known and her passing was not reported in the newspapers but she was just 52.

Christian and Susan’s youngest son was Arthur. Arthur, unlike his older brother, Charles, did not join the family business but instead worked in the Tea Trade. That did not seem to last very long as by 1891 he described himself, slightly vaguely, as “living on his own means”. And so it was that by the end of the century, Arthur, by then well into his 30s, unmarried and living at home with his widowed father, took a momentous decision. The conflict in South Africa between the British and the Boer republics had become increasingly bitter and violent and in 1899 Arthur Stehn, aged 38, volunteered as a Gunner in the Natal Naval Volunteers. Having enlisted and sailed to South Africa, the very next year he found himself trapped in the besieged “front line” town of Ladysmith. The conditions inside the besieged town were hellish and on the 19th February it was reported that Arthur had died of “enteric fever” - what we know as typhoid, probably caused by drinking contaminated water.

The Relief of Ladysmith by General Buller’s forces. Arthur Stehn was just one of 900 British casualties

After more than three months the siege was eventually lifted and it appears that Arthur’s body was repatriated as it was reported that his remains were buried in the Old Shoreham Road Cemetery. It seems likely that his father although by then in his 80s would, along with his two brothers and sister, have attended the funeral.

George Stehn was Christian and Susan’s second son and he too lived at 7 Brunswick Square for several years prior to his marriage in 1892. George like his brother did not join the family business but, unlike his brother Arthur, forged a highly successful career in the Tea Trade. He was initially a Tea Taster who made several visits to Ceylon (as it was then) and subsequently was for 15 years Manager of the Tea Department at Wilson, Smithett & Co of 21 Mincing Lane. The reward for all this hard work and dedication was being made a “Partner” in the Company in 1899. (By coincidence the same year that Arthur sailed to South Africa).

In April 1892 George had married Helenora Catherine Maxwell whose family came from Roxburghshire in the Scottish borders. The wedding was held at St Cuthbert’s in Hawick and it is presumed that Christian and George’s three siblings would have made the long journey up to Scotland for the happy event. It would also have been a unique event for Christian, as there is no record to suggest that any of his three other children ever married. When two years later Helenora gave birth to a son - Arthur Edward Stehn – he was Christian’s first – and as it turned out – only grandchild.

The third family tragedy, sadly, involves Arthur Edward Stehn. It wasn’t apparent at the time but the mid 1890s was a terrible time for a boy to be born. By 1914 they were young men.

He was part of that generation of patriotic young men who in the summer and autumn of 1914 volunteered to be part of Kitchener’s army.

Arthur Edward Stehn joined up on the 29th November, 1914 to fight against the Boches. We can only speculate about whether Arthur gave much thought to his Grandfather’s place of birth. In the early years of the war, Arthur was a young lieutenant in the trenches of Northern France and managed to escape with only minor wounds. He survived right through to November 1918 when it was reported that (by then) “Capt. A.E. Stehn, only son of Mr. & Mrs. George Stehn, was killed in action at Malplaquet on 8/11”. Yes, 8th November 1918, 3 days before the Armistice. The report went on that his remains were placed in the Malplaquet Communal Cemetery.

The Final Resting Place of Christian Stehn’s Only Grandchild

By the time of this tragedy, Christian Stehn had died as had two of his sons. Ellen, his daughter, had moved away and was last reported as a woman, single, and by then in her late 40s living as a boarder at St Christopher’s. Located in Blackheath, South London, St. Christopher’s appeared to be a kind of religious institution for women.

And so back to the house. Christian Stehn had passed away in the house in September 1901. He was 84. After the Stehn family’s departure, the house may have lain empty for two or three years but in 1904 a new family moved in headed by a lady with a rather mysterious name.

Chapter 6. Mrs Omega Perry

1904 – 1917

The Brighton Directories of the period indicate that in the first decade of the 20th century, 7 Brunswick Square was occupied by Mrs Omega Perry. “Omega” is an unusual name. Although gender-neutral, it was rarely “given” then (and rarely “given” now). Rare names are often helpful in historical research but references to Omega Perry are disappointingly scant. In fact, the only other discovered reference to a Mrs Omega Perry was in a March 1899 edition of the Brighton Gazette indicating her “arrival” in Brighton, in nearby 17 Lansdowne Place. The plot thickens.

In 1901, 17 Lansdowne Place was occupied by a Mrs. Mary A. Perry and so we must conclude that “Mary A.” and “Omega” are one and the same person. It seemed that, for reasons best known to herself, Mary Ann Perry used - for a while - the pseudonym, Omega.

We know from the census that by April 1911 Mary Ann Perry was living in 7 Brunswick Square. She was a 70-year-old “widow” of “independent” means who was born in Isleworth (then in Middlesex). Living with her in the house was her son-in-law, Charles A. Cullum, 48 years old and also of “independent” means. The word “independent” as used on census forms could be deliberately vague or evasive, perhaps a polite way of telling the enumerator to mind his own business. Amy Cullum, Charles’ wife and Mary’s daughter, was also living in the house. She was 40 and had been born in Hackney. The family group was completed by Dorothy Cullum, Charles and Amy’s 20-year-old daughter. She was born just down the coast in St. Leonards. There were just two maids and, presumably, plenty of space in their 11-room house.

The 1911 Census was the first census to be signed by the Head of House and so at the bottom of the form we see the actual signature of “Mary Ann Perry” (with not an Omega in sight).

What else can we glean about the Perry family? If we go back in time from 1911 and investigate that Hackney connection, we find Mary living in Mitford Crescent just off Amherst Road in Hackney. This was 1871, mid Victorian times, and judging by the occupations of those living in the vicinity this was a respectable lower middle-class neighbourhood. Mary described herself as “housekeeper” living in the house with her three young daughters – Amy is the middle one.

Does “housekeeper” imply this was her paid profession or was it just descriptive of her looking after the house and young family? She identified herself as “married” but - intriguingly there was no mention of any husband being present. Altogether as many questions as answers.

Following the St Leonards clue in 1881 we find Mary living in (nearby) Hastings. 9 Castle Parade is right on the seafront in Hastings very close to Hastings Pier (which had been completed a few years earlier). Number 9 seems to have been a house of multiple occupation. Mary was sharing her part of the house with daughter Amy. Amy was then in her late teens and “single”. There were just the two of them and Mary was by then describing herself as “widow” (she was in her mid 30s) and living on “dividends”.

It is unclear what those dividends were but by the turn of the century and the move to Brighton Mary seemed to enjoy greater financial security. Amy by then had married Charles Cullum and we might speculate that he brought money into the household. The family (Mary, Amy, Charles and Dorothy) lived initially in Lansdowne Place and were supported by four live in servant. This was followed by 13 years in 7 Brunswick Square. Mary finally died in the house on the 6th March, 1917 and in her will, probate was handled by Amy’s husband, Charles Alexander Cullum.

Chapter 7. The Courtenays

“He is known to the Police”

1920-1923

The Census taken in June 1921 confirmed that a Mr. Percy Courtenay was Head of House and that he, born in Lewisham, was 54. That Census of 1921 census sought much more detailed information about employment (where the person worked, the nature of the industry and their employer’s name) but, significantly, Percy revealed nothing - declaring “no occupation”. He was living with his American-born wife, Amelia who was aged 36 and their 13-year-old daughter Alfreda. A “friend and companion” of Amelia’s – Christina Augusta – was also staying in the house at the time. The rest of the household consisted of a resident cook and parlour maid. About Amelia Courtenay and Alfreda Courtenay, the records are silent. About Percy there is a cacophony.

“My old man said foller the van

And don’t dilly dally on the way

Off went the van wiv me ‘ome packed in it

I walked behind wiv me old cock linnet.

But I dillied and dallied, dallied and I dillied

Lost me way and don’t know where to roam

Well you can’t trust a special like the old time coppers

When you can’t find your way ‘ome.”

If there had been a hit parade in 1919, then “My Old Man” would have been top. It was performed as a comic song but we don’t have to delve too deeply to see that it’s actually about an impoverished Cockney couple doing a “moonlit flit” to escape the rent man. Hubby drives the van but wifey has to walk and, on the way, gets distracted and, blind drunk, can’t find her way home. It was wildly popular in 1919 and it was sung by the legendary Marie Lloyd. Marie Lloyd was the true superstar of the late Victorian and Edwardian Music Hall. Hoxton born and bred, she conquered first the East End then the West End, then Paris, then America. Her vocal talent and saucy humour captivated audiences everywhere. She was the consummate stage performer but as one contemporary newspaper put it with dry understatement: “her domestic life was unfortunate”. And her first husband was Percy Charles Courtenay.

Tilly Wood (Marie Lloyd was her stage name) was born into a respectable working-class family in 1870. Despite her family’s disapproval she was drawn to the stage from an early age and by 1886 was earning the huge sum of £100 per week. Quite soon after this she had the misfortune to meet a ticket tout from Streatham called Percy Courtenay. He was a good talker and he made her laugh. He also made her pregnant. After a whirlwind romance they married in Hoxton on 12th November 1887 - their daughter was born in May 1888. (Check the dates!) On the marriage certificate Percy claimed to be “Captain in British Army” (he wasn’t). It said she was aged 18 (she was 17). She was the earner but the space for her occupation was left blank. A reticence stemming perhaps from the suspicion that music hall performer was not a respectable profession for a woman. On their daughter’s birth certificate Percy described his occupation as “Commission Agent” although it seems unlikely that he did much if anything to justify that job title. A contemporary observer (female) described Percy as not handsome but slim and smartly dressed.

The marriage was under strain from the start. Percy was addicted to alcohol and gambling. He was not liked or trusted by Marie’s large extended family and he was jealous of and routinely angry with Marie’s music hall friends. He ran up debts and expected her to settle them. Perhaps it was the perceived humiliation of being a “kept man” but Percy frequently turned nasty.

Their tempestuous marriage provided the newspapers with a flow of sensational headlines and stories.

A typical one reported that Percy had been arrested outside The Prince’s Tavern in Wardour Street (the pub was owned by Marie Lloyd) where Percy had been waiting for her at the rear door. When he spotted her, he shouted “I’m going to murder you tonight. I will shoot you stone dead and you will never go on stage no more”. At the Marlborough Street Police Court, he was remanded in custody for a week. On another occasion he followed her to The Empire, Leicester Square and attempted to batter her with a stick, shouting “I’ll gouge your eyes out and ruin you”. He threw a glass at her in a Covent Garden pub. On yet another occasion Bow Street Police Court heard that Percy Courtenay “had caused a disturbance in his wife’s dressing room at Drury Lane and had threatened and kicked her”. His conduct was so menacing that she felt compelled to take out a “Restraining Order” on him.

At one point Percy was arrested as a member of a gang of three suspected of involvement in a robbery. The paper reported, damningly, that the man arrested, Percy Courtenay, “is the husband of Miss Marie Lloyd the Music Hall singer to whom he has been a source of trouble for many years. Until recently the popular artiste was allowing him the sum of £5 per week as a protection from his presence. He is known to the police as a racecourse frequenter of bad reputation”. He was living off her earnings and leaving unpaid bills to such an extent that she was forced to issue a public statement printed in many newspapers: “From this date, Miss Marie Lloyd will not be responsible for debts contracted by Mr Percy Courtenay. Signed Marie Lloyd”.

With all this in mind it does seem the height of irony that when Marie Lloyd began an affair with Alec Hurley, it was Percy Courtenay who initiated divorce proceedings, on the grounds of her adultery. After several separations they were eventually divorced in 1905.

Percy and Marie’s daughter - also named Marie - followed her mother on the stage, sometimes using her mother’s stage name and in 1907 she married. Her husband was a successful and well-known jockey: Harry “Tubby” Aylin (the wedding photos confirm that he was pencil thin). The wedding was a large and glamorous occasion but, significantly, “the Bride was given away by her Grandfather, Mr. John Wood”. Although Marie (jnr) had continued to use the name Courtenay, it is clear that Percy was not present at his daughter’s wedding. We must assume that he was persona non grata and not invited to either the wedding or the reception that followed at the residence of Mr and Mrs Alec Hurley (Marie and her second husband after her divorce from Percy). In a sad case of déjà vu, Marie and “Tubby’s” marriage soon ended in a similarly acrimonious divorce.

In her biography of Marie Lloyd, Midge Gillies describes Percy as a “maddeningly elusive figure” and after this Percy rather fades from the public eye. Marie had remarried and perhaps wished to expunge all reference to her disastrous first marriage and Percy - usually cast as the villain - perhaps thereafter preferred to keep a low profile. Whatever the reason news was scant apart from a brief report in June 1908. It announced that “the wife of Percy Courtenay” had given birth to “a daughter” in Manor Lodge, Thames Ditton. Rather curiously the wife is not named although we must assume that the wife was Amelia from America and the daughter was soon to be named Alfreda.

It is difficult to piece together what family life was like at 7 Brunswick Square. Percy no longer had access to Marie Lloyd’s wealth so it is tempting to think that perhaps New York born Amelia brought money to the marriage. The Census suggests that Percy, Amelia and 13-year-old Alfreda were together in the house in 1921 although by 1922 and 1923 the Directories indicate that it was just “Mrs Courtenay” living in the house. If that was so, where was Percy and what was he up to?

The answer might be found in a June 1922 edition of The Sutton & Epsom Advertiser. It was a report from the Epsom Magistrates Court that had been convened a few days after the running of The Oaks (one of the flat racing “Classics”) at Epsom Race Course. There had been huge crowds at the Course and following complaints a number of “Undesirables” had been arrested. Among them was a “bookmaker” named Percy Courtenay and his assistant who had been spotted behaving suspiciously. He was seen taking lots of bets but using a large bag with the (false) name Arthur Murray on the side. When two policemen approached, Percy is alleged to have said (according to a witness): “ We’re rumbled. The ‘tecs are watching” and with his assistant attempted to leave the Course. They were arrested and the following Saturday appeared before the Bench where Percy was “Bound Over for 12 Months”.

This story might shed some light on how Percy Courtenay spent his life during his residence in Brunswick Square There is, however, an element of doubt. The newspaper report gave Percy Courtenay’s age as “37” but “our” Percy would have been in his 50s at that time. It is possible that the reporter made a mistake or that Percy lied about his age but, equally it is possible that this is a different Percy Courtenay. This is possible. It would, however, be a remarkable coincidence for there to be two disreputable Percy Courtenays, at around the same time making a crooked living at racecourses.

For whatever reason – financial or personal - Percy had vacated 7 Brunswick Square by 1924 at the latest. However, it seems that he continued to live in the Hove district and when his time eventually came in September 1933 (reportedly from an accidental drug overdose) it was implied that he had been living in the area. He was buried in Hove South Cemetery. His funeral was reported, albeit briefly, in the local press where inevitably he was described as: “the first husband of Marie Lloyd”. Perhaps it summed up Percy’s niche in history.

Chapter 8. The Pre-Apartment Years

1924 –39

The neighbourhood was changing. The demand for large grand mansions had diminished. This would have been apparent to anyone living in 7 Brunswick Square as, in its immediate vicinity, Numbers 1, 2, 4, 10, 11 and 12 had, by 1928, already been converted into flats (almost exactly 100 years after their construction). Number 7 continued as a single residence until 1937 and during that period there were a number of relatively short-term residents.

A “Mrs Hally Craig” lived there for three or four years in the mid 20s. “Hally” is an unusual name – perhaps it was a version of Harriet or Hailey but whatever the reason and despite the rarity of her name Mrs Hally Craig left little by way of documentary record. Just one passing reference has emerged. In November 1925 a Grand Regency Fair was organised to raise funds for the Royal Sussex County Hospital. It was held in The Dome and, according to the Brighton & Hove Herald involved a “legion of helpers”. It was intended to celebrate Brighton’s Regency history and it was clearly a large-scale and lavish affair. Everyone involved was supposed to wear costumes of the Regency period. There was a “picturesque pageant” and a multiplicity of different stalls. One of the stalls was called “Ye Olde Stille Room” (apparently this was the room in great mediaeval houses where spirits were distilled and beer was brewed). One of the many assistant helpers in “Ye Olde Stille Room” was Mrs J Halley Craig. So, we may know little about Mrs Craig but we can perhaps imagine her in her Regency finery.

The house was empty for some of the time in the 1930s but for two or three years in the mid 30s was occupied by a “Miss Booth” about whom it has not been possible to find anything definitive. However, between the unobtrusive Mrs Craig and the concealed Miss Booth the house was occupied by someone who would have been very well known to the people of Brunswick Town.

For a year or maybe two around 1930/31, 7 Brunswick Square was home to the Rev. Stanley E. Kirkley MA. For almost 40 years Rev. Kirkley was the incumbent at the Anglican, St. Andrew’s Church in Waterloo Street.

Over the years he officiated at many weddings and funerals and one wedding in particular would have been of great interest. It was held on the 22nd August 1929 when Stanley Kirkley himself was married in his own church. Stanley came originally from Sunderland but his bride, Dorothy Eileen Payne, was a local lady from Hove and it seems reasonable to assume that Rev. Stanley and his wife Dorothy spent some of their early married life together at 7 Brunswick Square. The accommodation would have been conveniently close as the Church is just about visible from the back of the house.

Stanley Easton Kirkley of Keble College Oxford MA was ordained at Chichester Cathedral in December 1916. This was right in the middle of World War 1 and Rev. Kirkley was very soon recruited by the Admiralty as a Naval Chaplain for the remaining years of the war. Perhaps he was not entirely suited to Naval life for the Captain of one of the ships on which he served wrote on his record card, rather tartly, that “he [Rev. Kirkley] has not the faculty of getting in touch with the lower deck”.

Stanley survived the war but his family was not untouched. There is an octagonal wooden pulpit in the church with this poignant inscription: “This pulpit was given by the Rev. Stanley Kirkley MA vicar of this church in memory of his brother, Lt. Frank Kirkley MCRA, who made the great sacrifice in the 1914-18 war”.

It seems that Stanley was better suited to middle class civilian life for during his long incumbency at St Andrew’s (from 1923 until 1961) he developed a reputation as a caring and industrious priest. It was during his time that the interior of the church was much improved and beautified including the installation of “baldacchinos” (ornate canopies) inspiring the priest to rhapsodise that the church had become “a little bit of Italy in Waterloo Street”, perhaps suggesting that Rev. Kirkley was of the High Anglican persuasion. After their brief stay at 7 Brunswick Square, the Kirkleys continued to live in Hove until Stanley’s death in 1967 at the age of 84 and Dorothy’s in 1982.

The builders came in and did their work in 1937 which amongst other transformative changes ended the formal distinction between residents and servants. The Registration of 1939 suggests that there were 20 residents in the various parts of 7 Brunswick Square. Most were women but it did include three men who described their occupation as salesman/commercial traveller. In a sign of the times one other man indicated that he was an ARP Warden.

The Registration was a kind of mini-census designed to facilitate the issue of wartime ID Cards. It was held on the 5th September, 1939 and that date seems a very suitable one on which to end our story.

Note 1

Further information about the whereabouts and significance of the High Constable’s Silver Staff has emerged.

Firstly it can be confirmed that the High Constable’s silver staff now resides in a glass cabinet in the Mayor’s Parlour, Brighton & Hove City Hall. It is a splendid-looking artefact but more importantly it is now in the right place, for its presence there symbolises the handover of power.

James Martin was the last High Constable but like all his predecessors his position was an appointment. He was appointed by the Vestry. Each High Constable’s appointment began on Easter Tuesday and lasted for one year and at the end of each year his name would be etched in silver on the staff. James was appointed in 1854 but by then Brighton had an elected Council. James knew that he was as he put it “the last of the Mohicans”. He continued with the High Constable’s ceremonial duties for a number of years but recognised and - it seems - accepted the shift to democratic power. Hence the ceremony that he seems to have initiated when he formally and ritually handed over his staff of office to the Mayor. Perhaps the feeling of the town was caught by an 1857 article in the Brighton Gazette when the writer announced triumphantly: “Brighton has now 70,000 inhabitants. Brighton is now emancipated from the feudal sway of a High Constable and the humiliating designation of the “Whalebone Hundred”. It is a corporate town with a real Mayor and real Aldermen in real gowns, furs and gold chains”.

David Jackson holding the Constable’s Silver Staff at Brighton City Hall

The full length of the staff

Close-up of the plaque on the staff

Researched & written by David Jackson

January 2025, updated July 2025

Return to Brunswick Square page