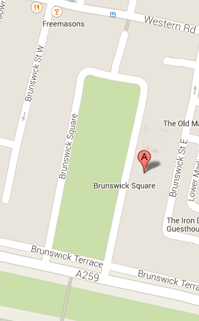

The Star of Brunswick - now 32 Brunswick Street West

Figure 1. The Star of Brunswick (as it is 2022). No longer a pub but the exterior is largely unchanged.

The Star of Brunswick was there from the very beginning.

A Tale of Two Pubs

Charles Busby’s master plan for Brunswick Town included the provision of two inns: The Kerrison Arms in Waterloo Street to the east of the square and The Star of Brunswick in the mews to the west. Antony Dale asserts that The Star of Brunswick was built with the estate and did not exist before it, so “probably in 1824” and whilst The Kerrison Arms had a “good class, almost fashionable” clientele, the other “was probably intended for the use of the inhabitants of the mews”. The Pub was built on a corner site on the West side of the mews street that is now known as Brunswick Street West. Dale’s implication that it was a working class pub makes sense, as most of the Star of Brunswick’s original clientele would have been the coachmen and stable hands then living and working nearby. It was definitely not, however, one of the cheap “beerhouses” that proliferated after the 1830 Beerhouse Act and it was also, by most accounts, a well managed establishment.

What’s in a Name?

Star of Brunswick: “an emblem which in outline is an eight-pointed or sixteen-pointed star but which is composed of many narrow rays … still used in the UK to surround the Royal Cypher on various badges” (Wikipedia)

Figure 2 A modern Star of Brunswick

Why was it named The Star of Brunswick and, indeed, who or what was the Star of Brunswick? Some 19th century pubs reference military or naval heroes: Nelson, Napier, Kerrison (one of Wellington’s generals); some reference particular trades or occupations: Basketmakers, Blacksmiths, Bricklayers; many reference William IV - the highly popular monarch who gave Royal Assent to the Act of Parliament that allowed just about anyone to open a public house. However, the rationale (if there ever was one) behind many other pub names is lost and so the difficult question forms how did The Star of Brunswick acquire its name? What follows is pure speculation.

There was a popular song of the period – a “glee” – composed by Samuel Webbe entitled “Hail! Star of Brunswick”. It was, supposedly, composed for Prince George (later George IV) and, we are told, he invariably “took his call” when it was sung in his presence. From that song it might be surmised that George himself was seen (and liked to be seen) as “the Star of Brunswick” and so, by extension, when in 1824 the Inn was given that particular name it could have been intended as a reverential nod to the - by then - reigning monarch.

Figure 3. Portrait of Prince George. Is he wearing a Star of Brunswick?

There is however an alternative less royalist interpretation. George was from the House of Hanover but it was his late wife (Caroline had died four years earlier) who was actually from Brunswick. During her life Caroline of Brunswick had been as popular with the people as George had been unpopular. George loathed her. They spent most of their married life apart with both suspecting and accusing the other of adultery. In a final vindictive act George excluded her from his coronation in 1820 and when Caroline arrived at Westminster Abbey, the doors – sensationally - were ordered to be slammed in her face. She died 19 days later. So perhaps we should see in the Inn’s name a veiled reference to the late but still loved - Caroline and by implication a deliberate and sharp snub aimed in the direction of a deeply unpopular king.

Figure 4. Caroline and George – respect or snub?

The Star of Brunswick - the Early Years

Back to fact and there certainly is documentary evidence to support Antony Dale’s judgement that the Inn opened in 1824. The Inn appeared on Busby’s original plan for Brunswick Town with the name Star of Brunswick and the Royal Institution of British Architects (RIBA) have a copy of Busby’s original drawing in their archive.

Figure 5. Busby’s 1820s drawing of the Star of Brunswick

It is certain that the Inn was built and functioning by the mid 1820s. The Brighton Gazette reported on an auction that was to take place in October 1826. A property from a bankrupt estate was to be auctioned and prospective bidders were urged to present themselves at The Star of Brunswick at 4.00pm on Saturday 14th October. Apart from confirming the actual existence of the Inn, it also suggests that it was more than just a coachman’s alehouse. It was a venue suitable for a meeting of people with the means to bid for property. It should also be pointed out that the Inn was quite a substantial and even handsome building on a corner site (see figure 1 above), situated just a few yards away from Architect Charles Busby’s house and office.

The Inn also offered accommodation. In the summer of 1831, a young man who was lodging at The Star of Brunswick advertised his wish for a “situation as a Captain’s servant on board an Indiaman”. The young man requests that any prospective employer should contact him via Mr Sargant (sic) at the Star of Brunswick. Henry Sergeant was the licensee at that time. The advert suggests that the accommodation offered at the Inn was cheap but respectable and one hopes that the young man, despite misspelling his landlord’s name, found a suitable “situation”. A census much later (in 1881) indicated that a group of 7 painters and decorators were staying at the Inn suggesting that it still was then and probably had been for most of the 19th century, an establishment that offered reasonably priced lodgings in its upstairs rooms.

Inns like The Star of Brunswick required a licence. That licence had to be renewed annually at a meeting of local Magistrates and all the evidence from the early decades indicated that The Star of Brunswick was a well managed pub. By Victorian times there was much concern about pub opening hours and a particular anxiety about Sundays. Pubs were required to close at 11.30am on Sundays and not serve alcohol “during the hours of divine service”. The Star of Brunswick seems to have played by the rules but many establishments did not. In August 1842, for example, on the “Annual Licensing Day” there was general complaint about pubs not closing at 11.30 but Mr Brooks (licensee of the Star of Brunswick) and also the licensee of the Kerrison Arms were complimented that their “houses were well conducted”. On the other hand, Mr Nye (licensee of The Wick) was roundly condemned for habitually allowing drinking during the time of divine services despite “frequent remonstrations” from the Constable. There was a slight regulation breach later that year and the Star of Brunswick’s licensee was reprimanded for “keeping it open too late at night”. However the Constable admitted that the house was generally “well conducted” and the Landlord promised to close on time in future. His license was renewed.

However well run a pub may be, it can never be entirely free of “incidents”. And one incident that occurred at The Star of Brunswick in June 1849 ended up before the Magistrates. John Ruff – a Fisherman – preferred a charge of assault against a Bricklayer’s Labourer named Adam Campbell. Ruff alleged that, the previous Tuesday in the pub, Campbell had punched two men before “without any provocation” striking the complainant. The facts of the case do not seem to have been questioned but under cross examination Ruff had admitted that he used to “keep company” with Campbell’s sister but had subsequently left her. The Magistrate fined Campbell a relatively modest 2 shillings and sixpence with 14 shillings costs. Throughout the 19th century there was a pattern of cases of assault being dealt with more leniently than cases of theft and perhaps in this case there were some mitigating circumstances. The men involved in this case were not Coachmen or Stable Hands but their occupations do give some credence to the notion that the Star of Brunswick was a pub with a mainly working-class clientele.

Figure 6: Artist’s Impression of a Victorian Pub Brawl

A Family Tragedy

For over 40 years in the middle decades of the 19th century the Licensees of The Star of Brunswick all came from members of the same extended family: the Barnden family. Throughout the 1840s William Barnden was the licensee and following his death in 1850 his wife Mary took over the licence. Mary had three sons: one was a Brighton Constable, another, Henry, was a Guard on the London to Hastings Railway Line and the third, John, lived at home in the pub with his mother. Mary’s existing ill health was exacerbated by a terrible event that took place in 1853 and in that same year her son, John, took over the licence. John was to hold it until his premature death in the late 1860s when the licence passed to his wife, Elizabeth Barnden. She later re-married and it was her second husband, James Tidey, who eventually took over the licence and held it until the late 1870s.

The tragedy referred to took place on the afternoon of the 13th of April. 1853. Henry Barnden, a Guard on the London to Hastings Railway, was the victim of a terrible accident. The train had not long left London Bridge Station and was steaming at about 30mph through a cutting near New Cross when Henry leant out to pass a copy of Punch magazine to his fellow Guard. As he did so - and stretching out too far - his head and body struck the side of a bridge with horrific and fatal consequences. The Brighton Gazette report (printed below) did not stint on grimly detailed description. The poor man’s remains were transported down to the station at Brighton where - with a terrible irony - the duty Constable who had to deal with the tragedy was Henry’s own brother. The poor man then had the melancholy responsibility of communicating the news to their distraught mother back in her pub.

Figure 7. Brighton Gazette (14th April, 1853)

Following his untimely death, testimony was paid to Henry’s “civility, sobriety and good conduct” and a fund was set up to assist his widow and three infant children “who were entirely dependent on him”. This accident must have had a devastating and long-lasting affect on the Barnden family and probably in the wider Brunswick Street community. It was also sufficiently newsworthy a story as to be revived fifty years later in a 1903 edition of the Gazette under their “50 Years Ago” column.

The Star of Brunswick – the Later Years

In the latter decades of the 19th century nothing quite as traumatic as the above seems to have befallen the Inn, its licensees or its customers. However, like any establishment dealing with the general public on a daily basis, The Star of Brunswick had its fair share of incidents. Theft seems to have been a perennial problem. In the 1860s, Samuel Gibbons, a Stableman lodging at the Inn, was convicted of stealing various articles from the Landlord. He got 3 months “hard labour”. In the 1870s, George Bransome, a “potman” at the pub was convicted of stealing money. Mrs Tidey, the Landlady, brought the prosecution herself when she discovered a “fiddle”. George had been delivering beer for the pub and pocketing the money himself. He pleaded guilty at Hove Magistrates and got “One Month Hard Labour”.

Theft of a rather different sort occurred in 1889. John Bentley – by then the Licensee – was summoned for selling a pint of whisky on the 5th April “which was not of the nature, substance and quality demanded”. Someone from The Public Analyst’s Office had entered the pub incognito and bought a pint of whisky from the barmaid for 2s/8d. Suspecting it had been adulterated in some way (or diluted), he took it away for analysis. Bentley appeared before the Magistrates and claimed in mitigation that it was “an accident”. He had been ill in bed and the pub had run out of whisky and (rather ungallantly) he claimed that it was his wife who had done it. He was fined 10 shillings. Three aspects of this story are of interest to the modern reader. Firstly, that whisky was sold by the pint, secondly that official Quality Control Tests of this sort were taking place. We perhaps should not be too surprised by this as, following huge concerns about the adulteration of food and drink in Victorian Britain, two quite stringent Acts of Parliament had been passed in the 1870s. We might though be surprised by the third aspect: the speed of the judicial process. The offence, the testing and the appearance in court all took place within a matter of a few days.

Finally, two small stories from the early years of the 20th century hint that the Star of Brunswick’s clientele may have altered a little during the first 80 or so years of its existence. It is important to remember that that area to the west of the pub had been open land in the 1820s but by the turn of the 19th/20th century that had been replaced by the solid, substantial avenues and squares of Hove. It was never a rough working-class alehouse but two short reports hint at some change. In 1907 it was reported that the customers of the Inn had donated 18s/6d to the Sussex County Hospital and a few years earlier in May 1903, The Gazette reported that following William Wilmer’s appointment as Constable for Hove, a Dinner in honour of the event took place at The Star of Brunswick. The word “gentrification” did not exist in 1903 but there was some evidence to suggest that both the street and its pub were in the process of being gentrified.

The Star of Brunswick 20th & 21st Centuries

This history is chiefly concerned with the first hundred years of the pub’s existence but this final section deals briefly with the second hundred including its decline and fall.

There is an intriguing story – difficult to verify – that back in the 1920s, 30s and 50s (the decades before decriminalisation) the pub was “a popular destination for members of the gay community”. Brighton Our Story - an organisation and website - outlines what we know about “Brighton’s queer past” and states that: “by the 1920s and 30s, Brighton was well established on the queer social map as the place to go and let your hair down. Pubs with a lesbian or gay clientele were flourishing, among them the Star of Brunswick in Brunswick Street West…” No evidence is offered in support of this assertion but equally it has to be said that in an era when there was a great deal of fear about what was then an illegal activity it is perhaps unsurprising that evidence in the form of letters or diary entries has yet to come to light.

Whatever the truth about the Star of Brunswick’s clientele, the second half of the 20th century seems to have seen the pub going into a steady decline until its closure in 2005. A property company bought the site for £450,000 and converted it for residential use. The building was not listed but fortunately its external structure was preserved and little changed. Also the original pub’s name has been subsumed into the building’s new name (see figure 8 below). It is comforting to think that the building we see today is recognisably the same building that Charles Busby designed almost 200 years ago and contains almost 200 years of quotidian human history.

Figure 8. Star of Brunswick House

Research by David Jackson (December 2022)

Return to Brunswick Street West page

Epilogue

History is a mixture of fact and interpretation and one highly intriguing “fact” emerged from the time of the Star of Brunswick’s early existence. It was in the form of a short article published in the Brighton Gazette on the 19th March, 1829. This is the article:

“The Star of Brunswick offers a reward of five guineas for a copy of a caricature which it says appeared in London but was bought up after a few hours. It represented a certain Duke and Secretary in the characters of Burke and Hare strangling the constitution …”

What should we make of this article? Everyone in 1829 knew about Burke & Hare. They were infamous. Even today most people have heard those grisly stories about the notorious body snatchers turned murderers who provided cadavers for Dr Knox’s Anatomy Lectures. Then it was the hottest crime story around: Burke had kept his appointment with the hangman’s noose just a few weeks earlier and, apparently, “burking” was the dark buzzword for that year. But who was the “Duke” and just as intriguingly, why would a Landlord of The Star of Brunswick be prepared to pay a large amount of money to purchase and display a copy of a cartoon in the taproom of his pub?

It was not difficult to identify the anonymous “Duke” and “Secretary” and also the sold-out caricature. The “Duke” was Prime Minister Wellington and the “Secretary” was Home Secretary Peel who together (mainly out of fear that there would otherwise be insurrection in Ireland) had pushed the Catholic Emancipation Bill through Parliament. To most modern readers a law that removed restrictions on Roman Catholic allowing them to hold important jobs and sit as MPs would seem fair and just but, in the Britain of the late 1820s, it was an intensely emotive and divisive issue. Just like recent debates about Brexit, it touched a raw nerve, raising fundamental questions about British identity and governance. The passing of the Act incensed many Anglicans and Protestants on both sides of the Irish Sea. It was a plot that would lead to “the destruction of the Protestant Constitution”. It would introduce “Popery”. The Earl of Winchelsea called his fellow Tory, Wellington, a “traitor” leading to a duel. The duel actually took place in March one Saturday morning in Battersea Fields although, happily, neither party was injured. And it led to a spate of savagely political cartoons - like the one below.

Figure 9. William Heath’s 1829 Etching: “Burking Poor Old Mrs Constitution Aged 141”

This seems to be the “caricature” referred to in the article. Likening the British Prime Minister and Home Secretary to a pair of murderers makes for a vicious cartoon. The power comes from the detail. Wellington and Peel use Burke and Hare’s exact modus operandi. One man pinions the victim down whilst the other suffocates her by holding her nose and mouth. Mrs Docherty (Burke & Hare’s known last victim) was aged 141 (aka The British Constitution since the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688) and her body will be just perfect for dissection and use by that sinister, cross-brandishing figure lurking behind the door. It was powerful then and it’s powerful now. Little surprise that copies of Heath’s etching sold out so quickly.

But why did the Landlord of The Star of Brunswick (perhaps it was Henry Sergeant) so want one of those copies? It is tempting to surmise that he was playing to the prejudices of his customers. Prime Minister Wellington was no longer seen as the hero of Waterloo and was widely unpopular with the British working class. Perhaps the Landlord felt that a strong government-bashing, catholic-bashing cartoon might appeal to his predominantly working-class customers. An interesting theory but … almost certainly wrong.

The original “fact” - the article in The Brighton Gazette - needed closer inspection. The article did appear in the Brighton Gazette but at around the same time the exact same article appeared in other local and regional newspapers, for example Exeter & Plymouth Gazette. It was common practice for local newspapers to cover stories of both local and national interest and often re-print copy from other papers. The implications though are clear: just because the report appeared in a Brighton newspaper it does not necessarily follow that it was a story about a Brighton pub. In fact, in all probability, the report is not about any pub anywhere.

The evidence for that comes from an unlikely source: the Caledonian Mercury. The edition of 9th March, 1829 contains a report about another newspaper called the “Star of Brunswick”. That newspaper - described as a “furious Orange Print” - had been “sent gratuitously” to the Heads of many Scottish Parishes. The Mercury pondered who was behind the distribution of this newspaper and speculated that Mr Butler, the Secretary of the Brunswick Clubs, may be able to provide the answer. The Brunswick Clubs were Protestant Clubs that sprang up in the late 1820s mainly to resist the movement towards Catholic Emancipation. In the propaganda wars being waged at the time, the “Star of Brunswick” newspaper sounds just like the kind of “Orange Sheet” whose editor would be prepared to spend five guineas to get hold of a copy of Heath’s etching.

It is a salutary reminder that in history facts can have different interpretations.