3 Brunswick Street West, formerly 30 Brunswick Street West, Hove

To complete the history of 30 Brunswick Terrace, we are returning to the property that began life as the stable attached to this main residence.

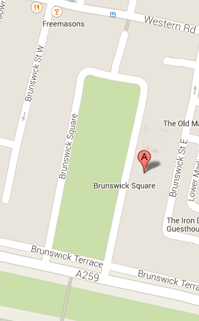

Recently, 3 Brunswick Street West has been described as a four-bedroom terraced house spread over 1,593 square feet, making it one of the largest, most desirable and expensive properties in the Street. It sits in a row of gentrified homes on what appears to be a cul-de-sac leading west off the main Street but there is a passage that is a public right of way conveniently leading into Lansdowne Place. No 3, formerly No 30 until 1925, leaves little evidence of its humble beginnings.

Compared to the rich findings of the Terrace residence, the stories of the stable occupants are scanty. As is usual, these residents are often not even recorded or when they are, the information is limited to births, marriages and deaths unless they have come to media attention. Our residents seem not to have gained notoriety! None were ever included with the main house data, their records coming from the stable address itself. Surnames are sometimes recognised by local families and so I do feel that even the basic facts are well worth mentioning along with a little embellishment.

The residents I tracked down were all Coachmen usually living along with their own family in the Stable. There was no evidence of other stable workers. A brief description of the daily lives of stable workers can be found under my history of 39 / 44 Brunswick Street West. I have no evidence here but it is known that the stable accommodation would sometimes be used to house the domestic servants.

Our sources sometime refer to the resident Coachmen as an ND meaning Non- Domestic or as a Domestic Coachman. Where this definition is not stated we cannot assume the exact status of their employment.

Advertisements for Coachmen appeared in local and national newspapers or they might be recruited directly from local stables or sometimes brought with the family moving, in this case, to Brighton. Job requirements might include to be ‘respectful, well presented, in good health and possibly married’.

The Domestic Coachman was an integral member of an affluent household, responsible for transporting family members and maintaining the stables. Their employment terms were outlined in formal contracts and typically these would include the following duties: safely transporting their employer and family; horse care including feeding, grooming and exercising; budgeting; cleaning and maintaining carriages and stable equipment; recruiting and overseeing the stable staff such as stable hands and grooms if these were employed. Typically for this they were paid between £25 to £60 per annum in the 1830s which equates to £2,285 to £5,485 in today’s money. He would be provided with a uniform or livery of two suits per year. Perks might include tea, sugar, beer and a laundry allowance along with heated accommodation above the stable. Time off would include for church attendance on Sunday, one afternoon per week and a day and a half once per month. Any evening outing would have to be approved by the employer.

One such contract I found included these minute details '1 frock coat, 1 vest, 1 pair breeches & gaiters – a suit of stable clothes consisting of a coat, vest & trousers, one hat (& one pair of boots & greatcoat) NB the latter not to be the coachman’s own at end of season - no poultry of any kind or description, or any living thing to be kept’.

The Domestic Coachman. A basic contract of employment

In contrast the ND or Non domestic coachman was not tied to a single employer and had greater flexibility to take both domestic and non-domestic work. When time and contracts allowed, opportunities arose to supplement their income by accepting private work such as driving for weddings and funerals.

The Livery Stables and Non-Domestic Coachmen

Between the 1830s and 1930s, several livery stables operated near Brunswick Square. It is more likely that our non-domestic Coachmen at No. 30 contracted with the closer Lansdowne Livery Stables located in Brunswick Street West but others included the Brunswick Inn and Stables established in 1834 at 1–3 Holland Road, the Wilbury Livery Stables established in the 1880s and some in Waterloo Street.

The contractual agreements with livery stables could be varied and might include paying a regular fee for the use of its horses and carriages or the Coachman might negotiate terms for privately owned horses to be boarded and cared for there.

As soon as the Railway arrived in Brighton in 1841 and Brighton became a popular seaside destination, another Coach enterprise, that of the Fly Proprietor, arrived on the scene. Although our Stable residents were never described as Fly Proprietors it could be that our Non-Doms would occasionally work for them. This would have similarities with Livery Stable employment. The Fly carriage was a lightweight, two wheeled horse-drawn vehicle used for hire, almost like a modern taxi, to transport visitors ‘speedily’ around the attractions and accommodations of the new resort. As well as the employment status of a coachman being quite variable, so also was the choice of available carriages.

The Carriages

Depending on the decade, family size and their particular needs and to reflect their social standing, we can imagine from the Terrace history the type of carriage that might be owned or used by some of our residents. In Brighton, where promenading along the seafront was a social activity, a stylish open carriage like the Victoria or Phaeton would have been especially popular for affluent couples looking to enjoy and be seen although a Brougham would provide more shelter. The main London carriage makers were Barker & Co., Hooper's, and Holland & Holland, with Long Acre being a central hub for the trade.

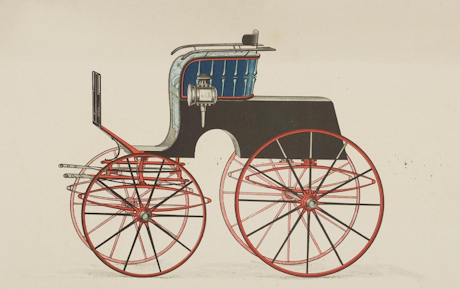

The Phaeton of the late-19th to early-20th century was a light, elegant open carriage with four wheels, often driven by the owner rather than a coachman. It was informal and ideal for promenading along Brighton's streets and the seafront if the weather allowed. Two spirited horses were required

The Stanhope Phaeton for the independent ‘show off’ owner

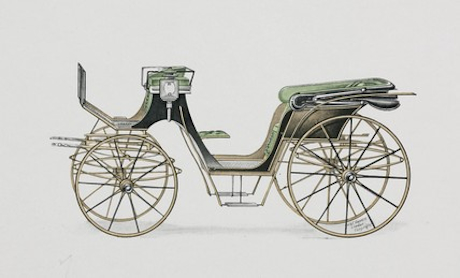

The Victoria was a low, fashionable, graceful carriage with four wheels, an open top, and a seat for a coachman. It had a folding hood in case of rain. It was a popular choice among couples to take them for a comfortable leisurely ride. A single horse or a pair of smaller, well-mannered horses were needed.

The elegant Victoria carriage

The Dog Cart was a practical, two-wheeled cart originally used for transporting hunting dogs that had been adapted for personal use. It had a higher, boxy seat for two passengers. It provided a practical, less ostentatious option and required only one sturdy horse.

The Dog cart: a fun run around

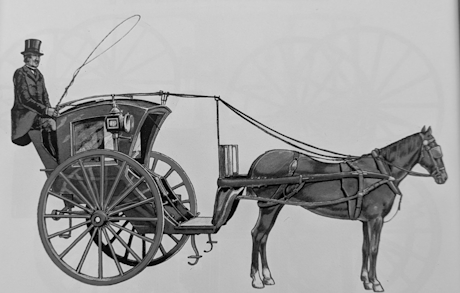

The Brougham was an enclosed, four-wheeled carriage with a small front window for privacy, often used in cooler weather or more formal occasions. It was an all year rounder and good for longer journeys. A single larger horse sufficed.

The Brougham offering privacy and shelter

The Landau was a more luxurious, four-wheeled convertible carriage with a split top that could be folded down at both ends. It was perfect for showing off at summer promenades, weddings, or high-profile events. It was used by wealthier families and usually drawn by a pair of high-quality, matched horses.

For the wealthy, The Landau

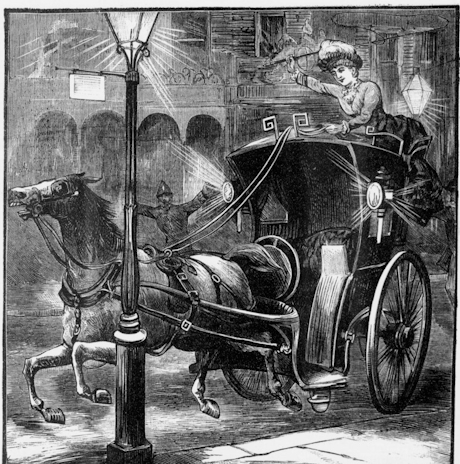

The Hansom Cab was primarily used as a public hire vehicle but privately owned Hansom cabs might have had appeal to a middle-class couple for convenience and modesty. It had two wheels and a small, enclosed seating area. It was a practical carriage for transportation around town and needed just one horse.

A female cab-driver

The Barouche is a large, open, four-wheeled, heavy, luxurious carriage drawn by two horses. It was fashionable throughout the 19th century. Its body provides seats for four passengers, two back-seat passengers and two behind the coachman's high box-seat. A leather roof could be raised to give back-seat passengers some protection from the weather.

More room in the Barouche

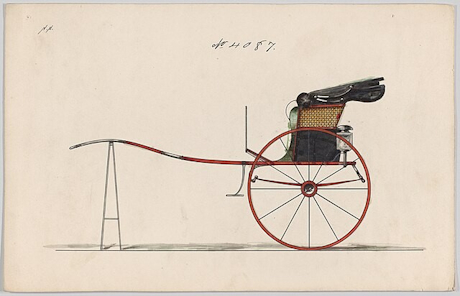

The Fly was a two wheeled public cab, the name used to denote a fast-moving coach similar to the stagecoach and very much resembled the Hansom cab. It was obviously the carriage of choice for use by the Fly Proprietor.

Fly Carriage, similar to the Hansom Cab

So as not to stray far from our stable history, I will just provide a rough estimate of costs for carriages and horses in Victorian times. Estimates are always difficult to make as they depend on exact dates, the quality of workmanship and the exchange rate sites used for calculation.

In today’s money low range carriages: a Dog Cart could range from £1,200 - £7,500 and a Phaeton £2,500 - £12,000

A mid-range carriage: the Brougham would be between £12,000 - £30,000; a Victoria £15,000 - £37,500 and a Landau £18,000 - £45,000

At the high end, a Barouche would be £60,000 - £150,000

Let us not forget that on top there is the cost of the horse(s) and their ongoing maintenance.

In today’s money: the working horse for a tradesman would equate to £1,200 - £4,500; a good carriage horse £5,000 - £12,000 and a high-quality matched pair £18000 - £50,000. The ongoing costs of feed, stable and care would total circa £2,500 - £6,000 per annum and if a Coachman and stable staff were recruited this would also add to the burgeoning burden.

With some rough calculations and comparisons, it seems that the cost of running a carriage equates to that of a car today and took a hefty chunk of the annual expenditure by our affluent residents.

The Motor Car

At the end of the 19th century, London was overrun with a total of 200,000 horses each producing 20 lbs of manure per day. This in turn caused a major health problem in the city. Obviously, this was not so acute in Brighton but for both places we can agree that the advent of the motor car was fortuitous!

In my research there has been no direct indication that any residents of the main house owned or used motor transport. However, to assess this possibility, we know that the motor car began appearing in Brighton in the mid-1890s and Brighton, as a progressive and fashionable seaside town, became an early adopter. Wealthy residents and visitors, including Londoners with second homes in Brighton, were among the first to own motor cars. The horse-drawn carriages previously used to transport residents and visitors from the railway station which had opened in 1841, were gradually replaced by motor transport.

Brighton, being at the forefront in this sphere, hosted on the 14th November 1896 the famous London to Brighton Emancipation Run which marked the official legalisation of motor cars in Britain after the repeal of the Red Flag Act. This law had previously required a man with a red flag to walk ahead of a motor vehicle. This event celebrated the new speed limit of 14 mph and it became the precursor to the modern-day London to Brighton Veteran Car Run.

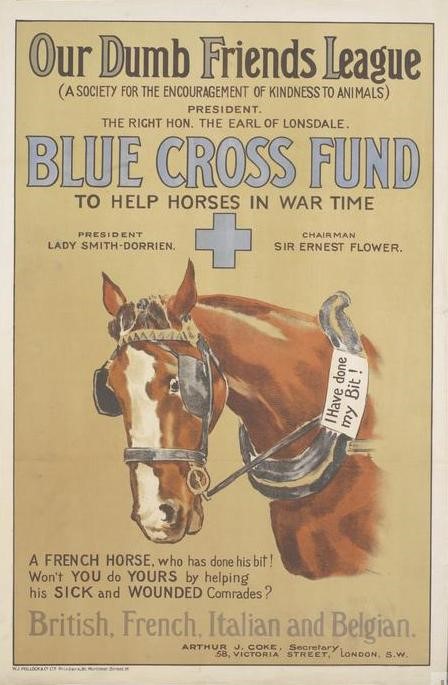

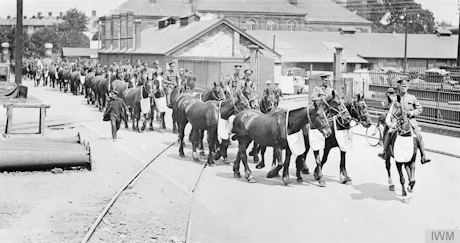

The 20 years from the mid-1890s until the start of the First World War must have been worrying times for anyone involved with horses and stable life. In 1914, at the outbreak of war, many horses in Brighton, like elsewhere in Britain, were requisitioned by the military for war service. The British Army needed thousands of horses for cavalry, transport and artillery, leading to widespread seizures of privately owned and working horses. Of these, only around a quarter were returned after the war. It was during the wars of this time, the Balkan and WW1, that The Blue Cross Fund was launched as a branch of Our Dumb Friends League in 1912. Their aim was to provide veterinary care to the horses and other animals used in the conflicts, working alongside the Army Veterinary Corp.

An advert for the Dumb Friends League

WW1 So many horses that they were roped together for ease of transfer

Horses heading to Southampton Docks

WW1 Transfer of horses across a river

And lastly, our residents, the people living at No 30 / 3 Brunswick Street West

In the 1861 Census, our first recorded family at the stable were the Birds, but we have no evidence of how long they remained there although we do know that Frederick Meyer and family were living at 30 Brunswick Terrace from 1859 until 1861. As the coachman’s employment status is neither given as domestic or non-domestic, William Bird could have been contracted to and working for the Meyer family during their residency.

William was born in 1824 in Walthamstow and at 37 years old was living at the stable with his wife Catherine aged 35, born in Blackmore, Essex and their five children. These were in 1861: the eldest Eliza aged 11, born in Essex in 1850; Emily Anne aged 9, Henry William aged 6 and Sarah aged 4 were all born in Paddington; then the youngest, their only child born in Hove was Charles William aged 2. Perhaps William Bird had been recruited by Frederick in London before they all moved to Brighton. The Meyers also had five children and five live-in servants and would certainly be in need of reliable transport.

For the 16 years from 1862 until 1878, when Thomas Wing and his sister Rebecca Wing arrived at the main house staying until 1884, we have no records of anyone actually in the Stable building until 1881. In the House History we deduced the Wings to have little social life and probably no need to employ a Coachman although they did have five servants. In the 1881 Census the Coachman ND (i.e. Non-Domestic) was recorded as a James Griffith, aged 57, born in Wales in 1824 and living with his wife Amelia, aged 47, born in Hatton, Suffolk, with their two children Susan aged 19 born in Middlesex, a dressmaker, and son James, aged 14. Interestingly the neighbouring Coachmen at No. 28 and 31 were also classified as ND. Were they all contracted to a local livery stable?

Soon after the Wings departed from the main house, the Gullands arrived in 1886. William Gulland living there for 20 years until he died in 1906 and his wife Julia continuing on in residence for another 25 years until 1931. They had no children and only three servants, but during this time three separate residents were recorded at the stables.

In 1886 we meet James Goodhew. Apart from street registers in that year and in 1887 we know nothing about James. He may have had no connection to stable work or the Gulland family.

In 1891 a Frank Collins is recorded as a Coachman Domestic Servant and so we can assume that his employer was William Gulland. Frank was aged 25 born in London Middlesex in 1866 and married to Alice, the same age and born in the same place. The neighbouring Coachmen at No. 28 and 31 were also now employed as Domestic Coachmen. By 1901, Frank had moved on to Queens Mews, Hove, with Alice and a son John aged 9, born in 1892 and daughter Mabel aged 8, born in 1893. Were these children born at our stable and had it perhaps become too small for this growing family?

Frank was still registered as a coachman at Queens Mews in 1911, living along with his wife and Mabel who had become a dressmaker, but John, now 19, seems to have left home.

It is not until 1906 that we see some stability in the occupation of our stable. We have a James Charles White, coachman domestic with his wife Kate. This was around the time of the death of William Gulland leaving his widow Julia in the maim house. James was born in Sussex in 1873 and Kate in 1876 in Winterbourne Stoke, Wiltshire. They stayed on at No. 30 for at least 24 years, until 1930 although the property numbering had changed and had become No. 3 in 1925. There is no record of children.

By 1939 James and Kate are living at 22 Linton Grove, Hove and James is described as a garage attendant as was their lodger, a Frederick Smith. A sign of the times!

Had Julia Gulland purchased a motor car while James was still employed by her and hence, he had gained the skills and was able to transfer to working in a garage?

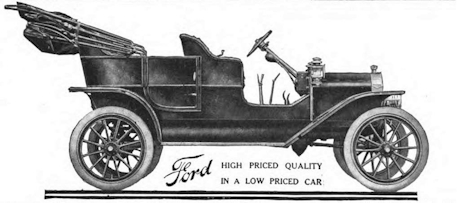

There are no further records of stable workers at what was now No. 3 but this could be explained by Walter Humphreys now owning 30 Brunswick Terrace and making, in 1932, a Building Control application for alterations to No 3. My first assumption that this was for changing from a stable to a garage or even private residence was proven wrong. A visit to The Keep shows it was for alteration of an already existing garage. It seems Walter just needed to change the frontage and door configuration. This means that a garage had existed while the Gullands were in residence and we can indeed contemplate that they, or just Julia, owned a car. Perhaps my other previous assumption that the Gullands had little social life was also incorrect and that they enjoyed travelling around the county in a Ford Model T.

A Model T Ford Car

Social activity

We can suppose that after a long day’s work our Coachmen sometimes popped in to the local tavern. This might be The Star of Brunswick (opened 1824), The Denmark Tavern (5 then 54 Brunswick Street West, opened 1864) or the Station Inn/ The Bow Street Runner (opened in 1867).

Perhaps Frank Collins in 1891 at the age of 25 joined his neighbours of No. 28 and 31, also Domestic Coachmen, for a beer in one of these Inns. Did James White who arrived in 1906 at No. 30, join our Edward Oxtoby who arrived at No. 39/ 44 Brunswick Street West as a Coachman in 1899.

I am told by a fellow researcher that the Station Inn was a little more refined hostelry and more likely to be the one frequented by Coachmen who were deemed as higher up the social ladder than other stable workers. But perhaps the Temperance Movement that was having an influential effect on the drinking habits of the manual workers may have sadly curtailed these well-deserved leisure activities.

To conclude, our stable has: accommodated the families of at least five Coachmen; stabled horses and protected carriages; possibly garaged motor vehicles and now provides stylish private accommodation. What will its future be?

Research by Anne Smedley, February 2025

Images from The Science Museum, The Imperial War Museum

Return to Brunswick Street West page.