26 Brunswick Terrace

What do the following have in common? Napoleon Bonaparte’s aide-de-camp, an illegitimate son of a British monarch, a High-Sherriff who was a collector of Judaica and an Irish Earl with one of the biggest funerals seen in Brighton.

The answer of course is that they all owned or resided at 26 Brunswick Terrace, although fortunately not all at the same time!

26 Brunswick Terrace lies at the very centre of the terrace facing out to sea and its façade remains almost true to the original design, although we shall see later in this house history that one owner in particular made alterations still visible on the exterior of the property.

The society pages of the Brighton Gazette tell us that by the mid-1820s the house was on lease for the Season (which in Brighton was Autumn through to Spring of the following year). The first mention of number 26 is in the Sussex Advertiser 1827, only four years after it was built when it is leased via Adnam’s estate agents. It is not until 1829 that an owner will keep the property for some years and use it for themselves.

Morning Post 11 August 1829

26 Brunswick Terrace was the residence of Lady Margaret Mercer Elphinstone Keith, (to give her full titles Comtesse de Flahaut, 2nd Baroness Keith and the 7th Lady Nairne) and her husband General Comte Auguste Charles Joseph de Flahaut de la Billarderie (to give him his full title). It is likely that they purchased the property around 1828 but leased the house through the 1829-1830 Season before residing there themselves.

Comtesse de Flahaut

The story of the Comte’s life could be lifted from the pages of a novel. Charles’ natural father was Talleyrand, a leading diplomat who worked for successive French governments from Louis XVI to Louis Phillippe I, spanning over 30 years. Charles’ nominative father was Comte de Flahaut who was guillotined in 1793. His mother Madame De Souza had fled to England in 1792 remaining until 1798 with Charles receiving an English education. Madame de Souza then went first to Switzerland and then Hamburg with her children. Talleyrand was widely acknowledged as Charles’ natural father and interceded to keep Charles safe during some of his early political indiscretions. On his return to France as well as having a successful career in the French army Charles gained a reputation due to his amorous liaisons. These included affairs with Napoleon’s younger sister Caroline and whilst in Warsaw around 1805 with Madame Potocka. Perhaps most notable was his long-term affair around 1810 with Queen Hortense of Holland, the daughter of Josephine, Napoleon’s first wife. (Hortense had married Napoleon’s brother Louis, who was later appointed King of Holland by Napoleon). In 1811 Charles and Hortense had a son, born secretly in Switzerland and brought up by Charles’ mother. He was later given the title Duc de Morny by his half-brother Napoleon III.

Comte de Flahaut

Meanwhile Charles held a distinguished military career in France. He had joined the cavalry in 1800, was at the battle of Marengo and was aide-de-camp to Murat at the battle of Austerlitz. He participated in Napoleon’s campaigns across Europe. By 1813 he was aide-de-camp to Napoleon Bonaparte and was present at the battle of Waterloo. Following the defeat of Bonaparte in 1814 and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy Charles, again with the protection of Talleyrand, fled to Germany and from there returned to England.

During this period in London, he met the future Lady Margaret Keith. By coincidence it had been her father Admiral Lord Keith who had taken charge of Bonaparte following his surrender. He had a very low opinion of the French and initially objected to the marriage.

Margaret was an independently wealthy woman, a regular at Court and had a close relationship with Princess Charlotte. She was considered to be strong willed, intelligent, forthright, and politically liberal thinking, views that perhaps attracted Charles. They were married in Edinburgh on 20 June 1817.

Perhaps as a result of their unconventional relationship (she knew of his past affairs and child and as a prominent French military man there was undoubtedly anti-French feeling from the British), they purchased properties in Brighton and Paris at a similar time, keeping a foot in both camps as well as in neither. The couple spent their time between Scotland, Paris, London and Brighton, the Chain Pier in Brighton allowing for a quick trip across the Channel to Dieppe. They had five daughters, two of whom died at an early age, and Charles’ son Auguste de Morny lived with them from 1829. They were welcomed in the great Whig houses when in England and when in Paris held regular soirees attended by both French and English aristocrats, writers and artists, among them Lord Byron, an intimate friend of Margaret’s who said, “I like Lady Keith extremely, because she likes me extremely”.

However, her forthright manner and the fact she insisted on wearing English dress meant she was not always appreciated at the French Court!

Comtesse De Flahaut/Lady Keith , Copyright image NPG

Around the same time Lady Keith purchased 26 Brunswick Terrace, King Louis Philippe came to the French throne. In 1830 Charles crossed to Dieppe from Brighton and restarted his career in the French army. King Louis Philippe promoted him to Lieutenant-General and to the Peerage with Charles becoming his aide-de-camp. The family continued to use Brunswick Terrace, whilst also establishing a residence in Paris, until in 1837 Lady Keith sold number 26.

By 1841 Lady Keith is reported as staying at 19 Brunswick Terrace, possibly at the same time that Comte de Flahaut commenced service as French Ambassador to Vienna but clearly the family maintained their Brighton connection. The Comte retired from army service and his ambassadorial post in 1848.

The Flahauts visited Brighton for the Season each year between 1848 and the mid 1850s as guests of Lord and Lady Willoughby d’Eresbys staying at West Cliff House, which used to stand at the bottom of Oriental Place. From 1851 the Comte’s services were again restored and from 1862 the Comte was French ambassador to London until he retired in 1864. His final role was as Grand Chancellor of the Legion d’Honneur. Both he and his wife died in Paris and were as prominent in French Society as they were in British.

La Promenade en Famille (Duke of Clarence and Mrs Jordan), cartoon by Gillray 'Image ©NPG'

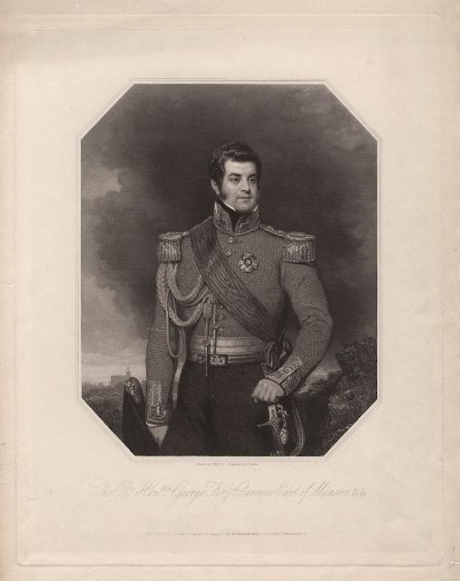

The next owner of number 26 was as prestigious as Comte de Flahaut and with just as complicated a pedigree. George Augustus Frederick FitzClarence, the 1st Earl of Munster (1794–1842), was the eldest illegitimate son of His Royal Highness William Henry Duke of Clarence and St Andrews (who subsequently became King William IV) and the actress Dorothea Jordan.

After a 20-year relationship his parents separated in 1811. His five sisters initially remained with their mother, whereas he and his four brothers were under the patronage of their father. They were all raised at Bushy Park, Richmond.

George FitzClarence had a strained relationship with both parents. Despite this he went on to have a distinguished military career, serving in the Peninsular War and the campaign against the Mahrattas in India and gaining the rank of major-general. By 1818, he married Mary Wyndham, an illegitimate daughter of the 3rd Earl of Egremont and the couple went on to have seven children.

When his father acceded to the throne in 1830 as King William IV, George as his first-born son was given the hereditary title Earl of Munster (created on June 4, 1831). Between 1830 and 1837 he was aide de camp to King William IV. Nevertheless, the Duke of Munster wanted to be acknowledged as the King’s son and preferably as Prince of Wales. He was notorious for his demands of finances and an expectation of title from the King and angled, unsuccessfully, to become Governor of India. His frustration and temperamental outbursts at being outcast, as he saw it, from his right of succession, due to his illegitimacy, was well documented and satirised.

Despite what might have seemed a life full of opportunity and patronage the Earl of Munster was by the late 1830s estranged from his father. It is known that the king was concerned about the behaviour of all his sons, who, perhaps following Regency fashion were given to drinking, gambling and debts. It has been suggested that the Earl of Munster may have been prone, like his grandfather King George III, to porphyria and poor mental health. He certainly suffered from gout and society reports frequently attribute his outbursts of temper to this condition.

In 1836 the Earl of Munster is reported in newspaper society pages to have been at 18 Brunswick Square for several months. Probably by the late 1830s immediately after Lady Keith sold 26 Brunswick Terrace the Earl of Munster was its owner and part time resident there as well as maintaining a London residence in Upper Belgrave Street.

Portrait Earl of Munster, Earl of Munster 'Image ©NPG'

The Earl of Munster is listed as one of the Commissioners for Brunswick Town between 1838 and 1842, acknowledging his connection to the town. Throughout this period his address is given as 26 Brunswick Terrace. His very limited role as a Brunswick Town Commissioner (he only had four attendances in four years) may have reflected his busy life with a range of engagements, but it seems likely given his personality and love of recognition that his role was mainly titular.

In the newspaper society pages he is reported as visiting to Earl Egremont in Brighton. The Earl was Lord Lieutenant of Sussex and as well as having his estate at Petworth had a mansion, East Lodge to the Kemptown side of Brighton. We may assume that the Duke of Munster maintained a relationship with his wife’s father even if not with his own and that his social and family life in Brighton may have been used in part to refute his need to be in London and to be in association with his father, the King.

The Cheltenham Onlooker, June 1837, provides a typical ‘gossip-column’ commentary about the relationship of the King and his family and particularly the long-term estrangement with the Earl of Munster. It makes it clear that the Earl only grudgingly attended at Windsor Castle because the King was dying.

By 1837 after the death of his father the Earl of Munster acted as aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria.

Between 1840 and 1841 he commissioned translations of works from Arabic and contributed to the works himself. He became a member of the Asiatic Society and amassed considerable works on the art of warfare from ancient Persian, Arabic and Indian writings.

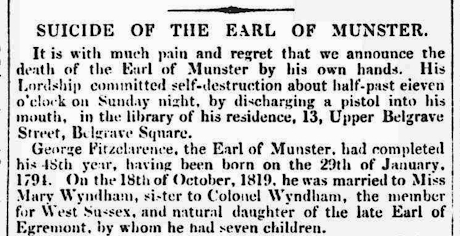

Suicide of the Earl of Munster , newspaper report

Despite his attributes his poor mental health is well documented and whilst mentally unwell he died by suicide in 1842 at his residence in Upper Belgrave Street, London. Almost every newspaper reported in graphic detail the circumstances of his suicide and his assessment by doctors of falling into depression and the sad deposition of the servants who found him.

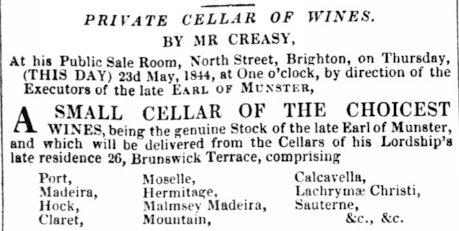

Newspaper advert Brighton Gazette May 1844 Auction of Fine Wines

In May 1844 we see that 26 Brunswick Terrace is still in the late Earl’s ownership as a local advert in Brighton is for the auction of fine wines to be delivered directly from the private cellars at 26 Brunswick Terrace.

Following the death of the Earl of Munster, 26 Brunswick Terrace appears again to revert to being leased over the social season and it is not until 1850 that the next long-term resident and owner will give us a true look at the property as well as the family who live there.

Philip Salomons (1796–1867) was the eldest son of a prominent family of Jewish financiers in the City of London who were merchants on the Royal Exchange. His father Levy Salomons was devout in his faith, living a short distance from the Great St Helen’s Synagogue where he was one of the principal wardens, a role which Philip was also to undertake. His younger brother Sir David Salomons was one of the founders of the London and Westminster Bank (a forerunner of NatWest) and the first Jewish Lord Mayor of London. He, like Philip, was on the Board of Deputies of British Jews. Philip appears to have resided with his family at Axe St and Crosby St in London presumably to remain close to the family business. As a young man Philip went to New York staying with Aaron Levy, possibly his father’s maternal line cousin, who was himself of Ashkenazi heritage, a financier, art collector, real estate dealer and philanthropist. In time Philip would follow the same trajectory of service and philanthropy.

When his father died in1843, Philip gained both more responsibility as well as independence. He is reported in society pages as early as 1843 staying for the season at 126 Kings Rd Brighton.

By about 1850 Philip Salomons had acquired 26 Brunswick Terrace. The reasons for this may have been twofold. Philip’s two younger sisters were each married to the brothers of Sir Isaac Lyon Goldsmid who had been instrumental in the creation of Brunswick Town. Philip would have been aware that living in Brunswick Town gave him equal social standing in a society that was still riven with antisemitism. (He already had a cousin, Joseph Salomons, living at 44 Brunswick Place.)

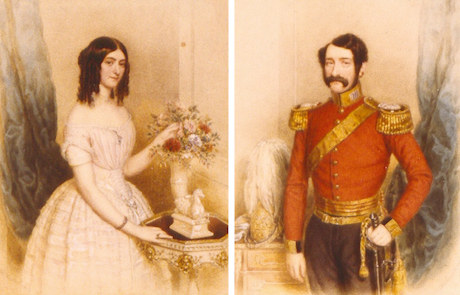

Double image of portraits of Emma Montefiore and Philip Salomons

Copyright Salomons Museum, Broomhill

Perhaps more importantly Phillip had recently married Emma Abigail Montefiore. At the time of their marriage, he was 54 yrs old, and she was 18 yrs old. Number 26 may have been a wedding gift for the couple to commence their new life together as they already had a house in Hereford Street, London.

Emma was the daughter of Jacob Barrow Montefiore a Barbados born merchant based in London and Justina Lydia Gompertz. Although born in London, it is possible she spent some of her childhood in Australia due to her father's business connections there.

In 1834 Jacob had been appointed by William IV as one of the Commissioners of South Australia becoming active in the early colonisation of the region. He first visited Australia in 1843 and then again in 1851. While in Australia he acted as agent for the Rothschilds and was in partnership with his brother Joseph as Montefiore Brothers of London and Sydney. (The brothers also founded the township of Montefiore in the Wellington Valley and there is a hill named after them in Adelaide).

The Saloman and Montefiore families were already connected at the time of Philip and Emma’s marriage as Philip’s brother Joseph (1802-1829) had married Emma’s cousin Rebecca Montefiore in 1824. (Their 3 daughters were of similar age to Emma).

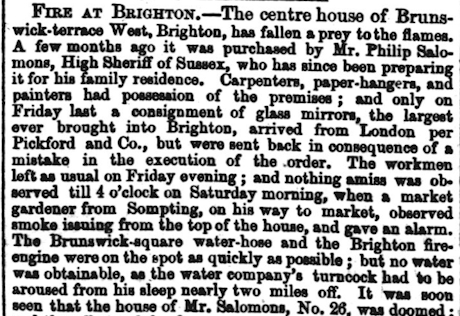

Whilst 26 Brunswick Terrace was fully renovated and furnished the family remained at 18 Brunswick Terrace where their first child David was born in 1851. However, their residency at Brunswick Terrace got off to a dramatic start widely reported in newspapers at the time, when in September 1852 a fire at number 26 gutted the entire mansion and caused damage to neighbouring properties.

Newspaper article 'Fire at Brighton' in 1852

(In an astute move there is a local auction in 1854 of furniture from the property. The date of sale suggests this is furniture that may have been damaged by smoke and is being disposed of before the entire property is refurnished.)

The Synagogue on the Roof

Philip was devout in his faith and the fire that had effectively gutted the property in 1852 allowed him the opportunity to add a rooftop prayer room (synagogue) to the house. Its position at rooftop would have been both practical (it did not detract from the original plan of the house) and would have also acknowledged the spiritual aspect that a place of worship was removed from everyday domesticity.

It has been suggested that Philip encountered opposition at the time from local Jewry for having what was effectively a private synagogue (which went against the tenets of a place of worship being open to all). Although there may have been some disquiet the main synagogue at that time was situated in Jew Street (moving in 1875 to Middle Street) and Phillip was not only an attendee but also on its Board of Deputies and it is assumed had permission from the Rabbi for his own prayer room. Moreover, as will be seen later his synagogue contained some acquisitions of Judaic artefacts that meant the room was as much a museum as a place of worship.

Philip was a magistrate and a Deputy Lieutenant of Sussex.

In the 1851 census Philip’s acceptance in society is evident as he describes himself as a Gentleman-at-Arms for the Queen. (He was first appointed in 1848.) Both the 1851 and 1861 census entries show him a good ten years junior than his true age, whether this was vanity on his part or an error by enumerators is open to question. He was appointed High Sheriff of Sussex in 1852 and, according to a local custom, was presented with twenty-four fire buckets (perhaps the irony did not escape him given his experience of the fire gutting number 26 in the same year).

By February 1858 Philip qualified as a Justice of the Peace for Sussex reflecting his sense of service to the local community. In addition, he served as a Brunswick Town Commissioner and maintained enough attendances to show a commitment and interest in Brunswick Town rather than attendance solely for show.

Philip and Emma had 3 children who were all born in Brighton, David Lionel b.1851, Laura Matilda b.1853 and Stella Rosalind Jeannette b.1855. A second son, Philip Montefiore, died as an infant. Nevertheless, despite having had four children in almost as many years, Emma maintained her skill as a society hostess. Although young, following her marriage Emma often acted as hostess for her brother-in-law David Salomons, Lord Mayor of London, in his wife’s absence due to her long-term illness.

In April 1856 when the Lord Mayor gave a banquet at the Mansion House in honour of Nathaniel Hawthorne, US Consul in Liverpool and author, his diaries, published as The English Notebooks show he and the Lord Mayor did not hit it off, but he does give a very lengthy description of the "beautiful Jewess who sat opposite”. Researchers now believe that this was Emma, whom he used as his muse for Miriam, the beautiful painter with an unknown past in The Marble Faun (published in 1860).

Sadly, Emma died in 1859 at their house in London and the children began to be looked after by Philip’s younger brother Sir David Salomons and his wife Jeannette, both in London and at Broomhill in Kent.

However, the 1861 Census shows Philip and his children all in residence at 26 Brunswick Terrace along with their retinue of servants including a Butler, Cook, 2 housemaids, 1 kitchen maid and 2 nurses. (It has not been possible to find out anything further about the lives of the servants in this household.) It is also interesting to note that the 1861 census has Jacob Montefiore, Emma’s father and his family back in England and staying at 12 Brunswick Square. We may presume, perhaps to be near to his grandchildren.

When Philip died in 1867 the children moved in with his brother David. When David died in 1873, David Lionel, Philip’s son, inherited Broomhill and the baronetcy. It is not known if Philip’s children used 26 Brunswick Terrace after their father died in 1867. However, in 1875 we see the property at auction at the request of Sir David Salomons who we must assume is Philip’s son.

Brighton Gazette, Thursday 02 December 1875

In his lifetime Philip Salomons gifted a valuable collection of Rabbinical books, collected by his father, Levy, to the Guildhall Library in London. The interior of his rooftop synagogue and many of its artefacts which were a record both of cultural heritage and artworks in their own right were largely purchased, following his death in 1867, by Reuben Sassoon who was both a near neighbour in Hove and who also maintained a private synagogue. Some items were purchased by the Central Synagogue in London for its new building at Great Portland Street. Although best known for his private synagogue Salomons was an avid art collector. The advertisement for his estate sale in 1867 described him as “that well-known Amateur” and reveals a collector with a good eye (possibly from the early influence of Aaron Levy). Amongst his collection were several Sèvres vases and cups, oriental vases, mounted rock crystal pieces, gold snuff boxes and bonbonnieres, French clocks, and tables and pedestals of rich marquetry

Examples of antique Torah finials once in Philip Salomons collection

(Interestingly the sale of 26 Brunswick Terrace in 1875 describes the former synagogue as a smoking room and in a later sale in 1903 as an observatory.) Today it is only the distinctive cupola shape of the former synagogue that remains visible on the rooftop at number 26.

It is likely that Lord Lurgan and his family were the next owners of 26 Brunswick Terrace. The 1881 census shows that Charles Brownlow, 2nd Baron Lugan (1831 – 1882) and his wife the Hon. Emily Anne, daughter of John Browne, 3rd Baron of Kilmaine (1823 - 1923) were residing at number 26.

The house was very full, the couple having 6 daughters, an Irish steward, a Russian governess and 14 servants a total of 24 people. The couple also had 3 sons.

Lord Lugan had succeeded to the Barony on the death of his father in 1847. He was a member of the Liberal party in the House of Lords and was Lord-in-waiting to Queen Victoria (the equivalent of government whip in the House of Lords) for William Gladstone’s first Government between 1869 and 1874. As head of one of Armagh’s leading families he also held the honorary post of Lord Lieutenant of Armagh from 1864 and in the same year was made Knight of the Order of St Patrick.

But it was not for his political appointments Lord Lurgan gained notoriety. He was well known in sporting circles, racing horses under the name Mr Stafford in his younger years but most famously for breeding and racing greyhounds. His most successful dog Master McGrath won 59 out of the 60 races he ran. The dog became so famous he has a statue in Lurgan, Co Armagh, had a song written about him, and Queen Victoria asked to meet him. It is said that Master McGrath’s death on 25 December 1871 ruined Christmas for thousands of Irish racing enthusiasts.

It is thought Lord Lurgan and his family moved to Brighton in 1878, probably to Brunswick Terrace, as his health declined. When the news of his death on 16 January 1882 was announced in Lurgan, the shops put up their shutters and the church interior was draped in black. The local newspapers talk of the deep sorrow of the town and of his generosity and charity. His funeral on Saturday 21 January 1882 was an obvious reflection of the respect and fondness for the Baron.

The funeral cortege left from Brunswick Terrace, the coffin on an open carriage, drawn by 4 horses and covered in beautiful wreaths. Following the coffin the procession was reported to be made up of 17 mourning carriages and about the same number of private carriages (local newspapers reporting it as one of the largest funerals ever seen in Brighton).

The service was held in St Andrew’s Church, Hove, conducted by the Rev. W M Brownlow, cousin of Lord Lurgan and curate of St Nicholas. His body was interned in the family vault in the church graveyard, however when a new St Andrew’s Church of England school was due to be built on this part of the cemetery, the vault and 5 Brownlow coffins were re-interred in Hove Cemetery on 1 May 1973.

Image of Master McGrath bronze statute Lurgan, Co Armagh

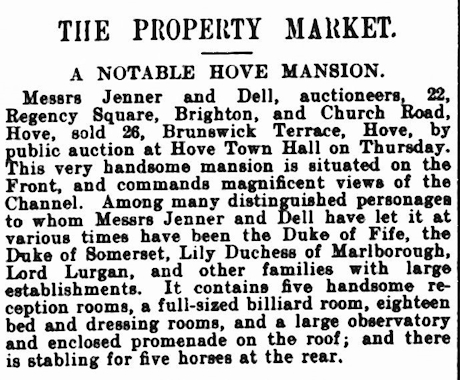

As we enter the twentieth century it is yet another auction announcement in the newspapers that tells us that not only is the freehold and entire house for sale but provides us with a snapshot of the great and good who have leased 26 Brunswick Terrace during the season up to that time (1903).

1903 Brighton Gazette advert auction of 26 Brunswick Terrace

The nineteenth century owners of 26 Brunswick Terrace reflect the larger scale Regency period evolving into the Victorian with lives that are exclusive, privileged and dramatic as well as entertaining. Were it possible to examine the lives of their servants, then of course a rather different story might unfold.

The owners and occupants of 26 Brunswick Terrace in the first half of the twentieth century are likely to tell us just as much about the influence of historical change upon their lives and the use of the property as the nineteenth has a story which will be continued at a later date…

Acknowledgements: Copyright permissions, National Portrait Gallery, Salomons Museum. Special thanks to Chris Jones at Salomons Museum, Broomhill, Kent

Research by Jo Smith and Rachel Pope (April 2025)

Return to Brunswick Terrace page