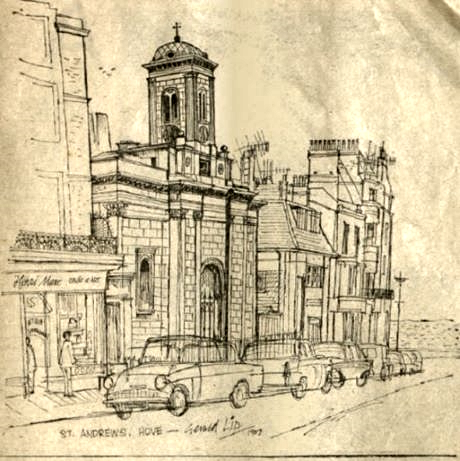

St Andrew's Church

A picture of St Andrew’s found inside the church – artist unknown

IN THE BEGINNING

Welcome to this study of St. Andrew’s, Waterloo Street, ‘the town’s second church dedicated to the patron saint of fishermen’. So how did St. Andrew’s Church get built on Waterloo Street, and why? Who were the people responsible for it and connected with it? What are its physical properties? What costs were entailed in its construction and maintenance? And what services and events has it offered to its community? Let us take a look.

RESPONSIBLE PARTIES

It was the prominent local clergyman Dr. Edward Everard who obtained permission to build a proprietary chapel (i.e. privately owned) on his land at the south-eastern end of Waterloo Street. This was in order to serve the development of Brunswick Town. Brunswick Town was built on the land known as Wick Farm, which went just up to the west of the parish boundary with Brighton. It was owned by the Reverend Thomas Scutt and was built between 1825 and 1828. The estate was envisaged as a complete town and therefore needed a place of worship.

Everard first gained permission for his speculation from the Vicar of Hove, Dr. James Stanier Clarke, and the Rev. Henry Plimley who was the Patron of the Living of Hove. An Act of Parliament on 3rd January 1828 authorised him to erect, at his own expense, on his own land, a Chapel of Ease (i.e. a more accessible, convenient place of worship for the local congregation) to the Parish Church of Hove, to be called St. Andrew’s Chapel.

The Act gave him legal ownership of the building and also made him responsible for its upkeep. He was empowered to appoint a Perpetual Curate (the name given to a minister of a Chapel of Ease) for a period of 40 years and took on this position himself. The chapel was licenced for the celebration of baptisms, the ‘churching of women’ (a blessing given to mothers following recovery from childbirth) and burials. (Licence to celebrate marriages was not given until 1st March 1920.)

Charles Busby was the architect of Brunswick Town and had expected to be the designer of the chapel. However, Everard and Busby fell out when, despite his assurances that Busby would be given the commission for the building of the Sussex County Hospital, Everard had been overruled and the commission had been given to Charles Barry rather than Busby, who felt betrayed.

When considering the building of St. Andrew’s Church in Waterloo Street therefore, Everard decided in favour of Charles Barry who had worked on the façade of the hospital and St. Peter’s Church in Brighton. Barry would later be best-known for his work on The Houses of Parliament. Excavation for St. Andrew’s began in 1827 and it took a year to build. It was consecrated by the Bishop of Chichester, Dr. Carr, on 5th July 1828, after which it was open for public worship. ‘It was soon to be one of the most crowded and fashionable churches in the district.’

Blue Plaque dedicated to Sir Charles Barry

The cost to Everard for this commission was £6,000. We will return to the church’s finances later. First, let us consider what this outlay produced.

THE EXTERIOR

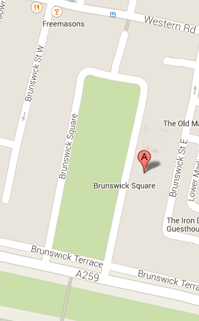

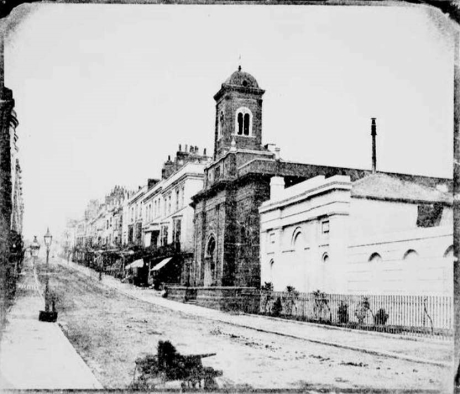

Waterloo Street from the James Gray Collection – Courtesy of Regency Society

Inspired by the Renaissance architecture Barry had seen on his grand tour, St. Andrew’s is the first example of the Italianate Quattrocento revival in England. It was ‘the gem of all Hove’s churches, graceful and distinguished inside and out, and of manageable size’.

The building materials used were brick and ashlar (finely cut stone blocks).

The west-facing entrance door is set beneath a round-headed arched opening between twin pilasters (decorative rectangular columns), the outer pair of which serve as quoins (corner building blocks) for the adjacent recessed walls. There is a small domed bell tower with a lead roof and clock faces. A later extension, Chapel Mews, alongside and behind the church, provides an early example of the use of beach pebbles as a building material.

THE INTERIOR

The interior was initially very simple; that of a plain box-like Regency preaching house, with only one gallery at the west end of the church and a nave. There was no chancel. The chief feature was the altarpiece at the east end of the nave, consisting of three round-headed niches containing panels inscribed with The Ten Commandments, The Lord’s Prayer and The Creed. These were flanked by a pair of simple pulpits or preaching desks, but without prominent curved staircases to them.

The organ was the work of a Mr Lincoln, organ maker to the Prince Regent (later George IV). There were box-pews throughout. On the north side of the building was a narrow schoolroom fitted with desks. This was later converted into a vestry. Under the chapel a series of well-built brick vaults was constructed with racks for coffins. Memorial tablets were placed on the nave walls.

For some years only minor alterations were made. For example, The Lord’s Prayer was replaced by a cross and the two large pulpits on either side of the altar were removed.

However, in 1869 the church was radically restored by the Rev. Daniel Winham, who replaced the seating with open carved oak benches.

Carved oak benches – Photo S.M. Allen

According to a description in 1874 the wall behind the altar was decorated with a ‘most remarkable and awe-inspiring’ painting of a black cross on red background. A document dated Sept. 1881 gives notice of intended building on a piece of land adjoining the church at the rear and east side, and of alterations to the interior.

Winham spent £2,000 of his own money on the acquisition of this land, with a view to enlarging the chapel. He commissioned Charles Barry’s son to erect the chancel which exists today. He constructed a sanctuary in the centre, additional accommodation for the congregation in the south and a place for a new organ in the north. (An elaborate organ case, beautifully carved with flowers and fruit, was added in 1889.)

The sanctuary was separated from the other two portions of the chancel and from the nave by wide arches, supported by Ionic columns. A dome was added, with gold stars on a blue background.

Blue dome with gold stars – Photo S.M. Allen

The east end was extended into a small, curved apse framing the altar, which was lit from above by a semi-circular window set in a domed roof. Twelve windows depicting the twelve Apostles were added, the work being done by Hardmans of Birmingham. All this transformed the interior from its former severity.

Stained glass windows of saints – Photo S.M. Allen

Father Kirkley became the vicar in 1923. He decided the interior was too dark and embarked on an ambitious programme of remodelling. All but two memorial tablets were removed from the nave to the porch. Heavy stencil work and coloured heads covering the walls and ceilings were painted over with light stone colour. Dark and gloomy glass surrounding the figures of the Apostles in the nave was replaced by Italian glass roundels (brought by the vicar from Venice).

The choir stalls were moved from the centre of the chancel to give a better view of the altar, and the wooden floor raised and re-laid in York stone slabs, as was the sanctuary and chancel floor. Two separate clergy stalls of solid carved oak were added in the chancel. New bronze altar rails were added as well as two four-foot-high bronze candlesticks and a 14th century sanctuary lamp. A new bell, new pulpit and canopy of solid oak were added. In his aim to re-create ‘a little piece of Italy’, he employed W. H. Blacking in 1925 to design a baldacchino, or canopy, over the altar, with a shallow pediment on fluted Corinthian columns.

Sanctuary and Baldacchino – Courtesy of Regency Society

‘We All Partake of the One Bread’ on Pediment – Photo S.M. Allen

At the west end he inserted a new marble font also surmounted by a similar but smaller baldacchino.

Font with Baldacchino – Photo S.M. Allen

In 1927 an application was made for the erection of a stained-glass window on the south side of the chancel showing a representation of The Annunciation.

Stained Glass Window of Annunciation – Photo S.M. Allen

The roof was refaced, the roof repaired and the organ reconditioned.

FINANCES

Now we return once more to the question of money. What were the costs of alterations and maintenance, and where did the money come from?

Expenses Incurred by Alterations and Maintenance

Everard had, we remember, paid £,6000 as his initial outlay for the project. But it was the Rev. Winham who incurred some great expense for his alterations and repairs. After his £2,000 payment for the extension to the building, the cost for his various additions amounted to over £5,203.

About 150 members of the public raised £2,328, the balance of £,2875 being paid by Rev. Winham himself. Members of the congregation gave the twelve windows depicting the twelve Apostles.

Rev. Kirkley’s costs were also considerable. The total cost of his repairs and alterations in around 1925 was £4,000, ‘every penny of which was given by those who worshipped in the church without recourse to bazaars’. Further expenses were incurred over his remaining time with the church, such as the regular need for roof and organ maintenance.

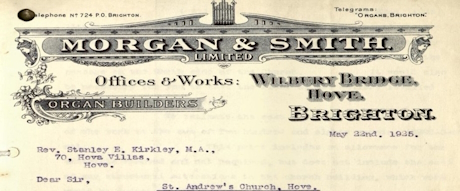

Part of Morgan and Smith’s Estimate for Organ repair 1925 (£280)

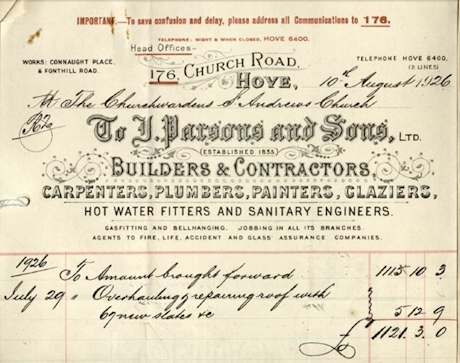

Part of Parsons’ invoice for roof repair 1926

To remind ourselves, then, of the kind of payments needing to be made by the church, we can see from a 1937 document that they included: repairs (the organ and the building), the incumbent’s stipend, wages for the verger and cleaner, organist and choir expenses, coal, gas, electricity, water rates, fire insurance, printing, altar wine and bread, candles etc., laundry, as well as contributions to the sick and poor fund and other outside charities.

In June 1954 it was noted that the current income received by the vicar was £380.11s. 5d. p.a. and that this was short of the usual £500.

A request was made to the Diocese by the Parochial Church Council that the situation be remedied and that, in fact, a fairer payment of £550 should be considered, particularly since there was no vicarage provided. The Diocese was therefore asked to pay half of the balance required i.e. £85.

In 1963 and 1964 Rev. Evans, the last incumbent, needed to put out an appeal for £3,000 and then £4,000 towards much needed work ‘to help towards preserving this unique church in our Borough’.

The Raising of Funds

Some of these expenses could, of course, be covered by the usual ceremonies provided (e.g. for baptisms, the churching of women, burials and (later) marriages). The church collections were valuable too. Sometimes bequests and legacies from wealthy members of the congregation helped. Donations from The Friends of St. Andrew’s and various charities were appreciated. Occasionally, an anonymous donor would come to the rescue, as in 1947, for example, when one such contributed to the restoration of the organ.

Some of Rev. Winham’s costs were obtained through public subscription. A fundraising event could also prove useful. For example, a Hove Bazaar was reported in 1908 for the sale of works in aid of funds for St. Andrew’s Church at the Town Hall by Lady George Nevill, ‘who wished it every success’. The most productive source, though, was the system of pew rents.

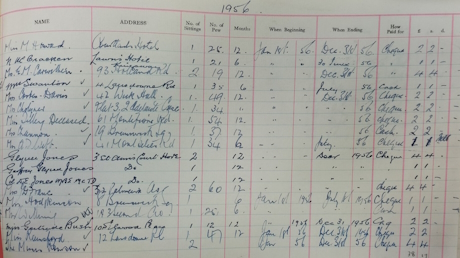

Pew Rents

The 1828 Act set aside 80 seats as free. (These, of course, were in or under the gallery.) The seats in a better position at the front were to be sold to prospective, wealthier, members of the congregation and the Act stipulated that these rents should bring in £150 p.a. Out of this the curate had to pay the salary of the Clerk of the Chapel. The remaining pew rent belonged to the proprietor of the chapel who could let or sell them off as he pleased. Often the seats were put up for auction and sold to the highest bidder ‘though only bids from people of quality would be accepted’.

In 1851 the Ecclesiastical Census recorded that 350 people were attending the church in the morning and 300 in the afternoon. There were 420 pews and 340 were subject to pew rents, meaning, again, that 80 of them were free, but the remaining seats were rented for between £10 and £15 a year. In the 1800s the church was the place to be seen for your contributions.

A register of pew rents was started in 1942. We find several titles amongst the contributors (Sir, Lady, General, Colonel, Major, Field Marshall) with local addresses predominating in the grander properties. Some of the ‘great and good’ in 1942 included Lady Hutchinson and Sir Cecil Bingham. In 1947 two guineas was paid per person per seat for the year and this price remained the same throughout a twenty-year period. Payments were either for a couple or single person.

Pew rent register 1956

From 1948 to 1962 we can see a gradual dwindling of recouperation by this means (from £108 3s. 0d. to £33 12s. 0d.) with only 17 payments made at the last date, only 2 addresses being in Brunswick Square and Terrace. This contribution was significantly lower than the previous century when the congregation was larger and more affluent.

As time went on therefore, it is clear that fewer people were paying for pew rents, church attendance was falling and the nature of the residency in the Brunswick area was changing from its ‘grand house’ image to one of more flats and bedsits.

PEOPLE

Congregation

Initially, of course, we have seen that Brunswick Square was an upper-class development and, because of the social success of Brunswick Town as a place of residence, soon had the most aristocratic congregation of any church in Brighton or Hove. On one occasion in 1828 the pews contained three Dukes and three Duchesses (those of Bedford, St. Albans and Roxburgh).

By the 1840s the congregation included the elderly Duchess of Gloucester (sister of George IV and William IV and aunt to Queen Victoria), the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and their daughter Princess Mary. The Duke of Cambridge was known for his eccentric manner of commenting loudly on passages in the service, though he himself may not have appreciated his volume, owing to his extreme deafness. Nevertheless, its popularity as a place to be seen grew. An Ecclesiastical Census in 1851 recorded that there were 420 seats and the morning congregation numbered 350 attendees, while 300 came in the afternoon.

A rather splendid wedding was announced in 1928 which was that of Mr. Frances Russell Clifton (former officer in the Indian Army) to Miss Gwendoline Muriel Sharp who ‘looked charming in a French model dress of brown georgette’ and ‘carried a posy of lilies of the valley and rosebuds.’ They honeymooned in Paris. The Rev. Stanley Kirkley presided.

Burial Registers and Monumental Inscriptions

A look at Burial Registers kept by St. Andrew’s shows similar examples of high-class society. Under Everard as Perpetual Curate we have a record, for instance, of The Honourable Caroline Anne Hughes of Brunswick Terrace, dated April 25th, 1832, dying at the age of 14.

We also see a Sir George Dallas of Brunswick Square recorded, dated 21st January 1833, aged 74 years. Robert Cunninghame is dated as 8th Sept. 1836, aged 66. Under Owen Marden, we have a record of Sir Ralph Gore of 26 Brunswick Square, the date given as April 1842. He died aged 83 years.

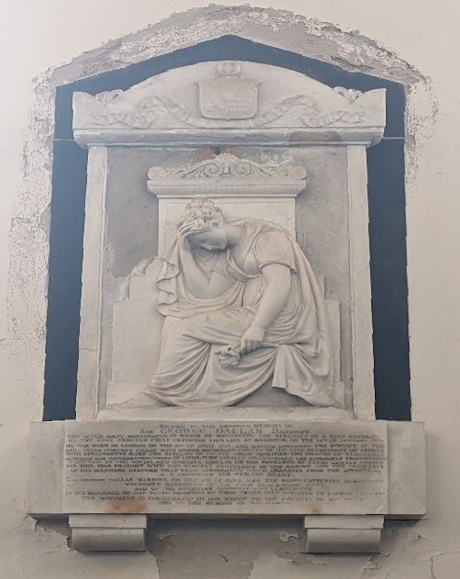

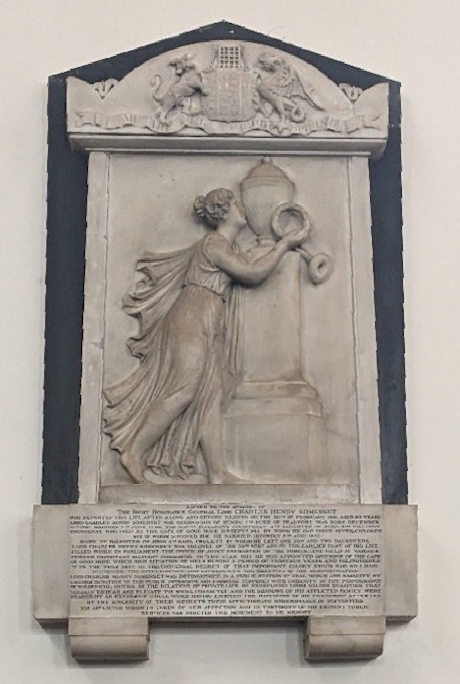

Memorial to Sir George Dallas – Photo S.M. Allen

In 1844, we see the name of the Rt. Hon. Lady Elizabeth Parsons of 6 Adelaide Crescent, dated 16th Dec. aged 36. Reminding us of the status of its congregation, the death was recorded in a local newspaper in 1905 of a Mr. H.P. Holford, ‘a well-known and highly esteemed resident…A memorial service will be held at St. Andrew’s Church today at 2 o’clock’.

Regarding monumental inscriptions, we have, for example, Lt. Col. G.J Gillespie of 4th Madras Light Cavalry, dated 17th Dec 1826, aged 48. There is also the Rev. Richard Roberts of Sporle, Norfolk, dated 13th August 1831, aged 68, as well as William Walter Vane Esq., Lieut. Col. Coldstream Reg. of Guards, dated 11th April 1839, aged 71. Sir Ralph Gore, mentioned above, had a memorial designed by A.H. Wilds, architect, and W. Lambert & Son.

Two particularly significant memorials are those of the aforementioned Sir George Dallas (a poet and political writer and a General of the East India Company’s Army) and Lord Charles Henry Somerset (1814-1826) who was Governor of the Cape of Good Hope, a soldier, politician and colonial administrator. These two memorials, to be seen on the nave walls, were the work of John Ternouth (1796-1848), known for his work on one of the four panels at the base of Nelson’s Column, depicting the Battle of Copenhagen as well as the figure of St. George and Britannia at Buckingham Palace. (Sadly, he died of typhoid before the memorials were installed.)

Memorial to Rt. Hon. Gen. Lord Charles Henry Somerset – Photo S.M. Allen

The Vicars (Incumbents or Perpetual Curates)

Between 1828 and 1962 we can identify 10 incumbents:

Edward Everard was in this position for 10 years (i.e. until 1838), Owen Marden for 18 years (until 1856), William Henry Rooper for 7 years (until 1863), W.H. Kerslake for 3 years (until 1866), Henry Beaumont for 2 years (until 1868), Daniel Winham for 26 years (until 1894), C. A. Moull for 12 years (until 1906), John Paget Davis for 16 years (until 1923), Stanley E. Kirkley for 38 years (until 1961) and in 1962 Arthur Evans took up the position.

Certain of these add to our understanding of the prestigious nature of their positions. For example, the Roopers, Beaumont and Winham were Brunswick Commissioners. This was a body set up in 1830 by the Brunswick Square Brighton Improvement Act and the activities of the Commissioners had an impact on most features of daily life in Brunswick Town, including policing, road repairs, refuse and the uniform appearance of the estate. Commissioners had to have high property qualifications, i.e. the owning of freeholds or leaseholds on the estate thus marking high social status. William Henry Rooper attended 59 meetings and chaired 4 times. Beaumont attended 126 meetings and chaired once. Winham attended 9 meetings but did not chair any.

The longest serving incumbent of St. Andrew’s was the Rev. Stanley E. Kirkley, who served for 38 years.

Let us take a closer look at some of these incumbents.

Revs. Rooper:

We need to remember two members of the Rooper family: Thomas Richard Rooper and his son, William Henry Rooper.

Despite poor health, Thomas Richard Rooper was involved in many activities to improve the lives of the local people. He regularly visited the school in Ivy Place as well as The East Hove National School, which became Farman School in 1878. His memorial at St. Andrew’s old church credits him with ‘an unremitting endeavour to alleviate the sorrows of the afflicted and distressed and to elevate the religious and moral condition of the children of the poor by improved education’.

Largely due to his ill health, Thomas Richard Rooper left his parishioners in the care of the curate, his son William Henry, who lived up to the family’s good reputation. A later move to Bournemouth produced the following tribute: ‘The name Rooper is widely known in connection with philanthropic works and intellectual pursuits’.

Rev. Beaumont:

Unfortunately, the same high regard might not be given to the Rev. Dr. Beaumont who has something of a scandal attached to his name.

It was reported on the 3rd Oct 1867 in the Brighton Gazette that a court hearing had declared that a certain Captain Henry Woodhead was accused of an unprovoked assault on the claimant, the Rev. Beaumont, incumbent of St. Andrew’s Church. The assault took place on the Esplanade, opposite The Norfolk Hotel.

Initially, Stuckey (for Woodhead) decided to plead not guilty, but that the act was justified. But due to the possibility of the assault being shown as severe, and going on to trial at the Sessions when Stuckey would have to provide justification for the act, the defendant agreed to plead guilty and pay the penalty for a mild assault, though without provocation, if no further details were gone into, ‘having regard to the feelings of all parties’. Only the circumstances of the assault itself were to be examined.

However, despite Stuckey’s objections, the Reverend’s solicitor (Lamb) decided to provide some information in order to prove that the act was premeditated and to better determine what punishment to award, and subsequently read aloud the following letter:

14th May,1867.

"SIR, I have shown the letter you wrote to my daughter to several of my friends, and also the lying and hypocritical note you sent to me. Their opinion coincides with my own, that anyone who, under the garb of religion, takes advantage of his position to pervert the mind of a young and unprotected girl, is a most consummate scoundrel and hypocrite, and I shall proclaim you as such in society in this place, and now give you to understand that if, after the receipt of this letter, you show yourself in Brighton, or ever profane the religion you disgrace by doing duty in any church or elsewhere, I will make it my duty publicly to insult you, even at the church door, and at the same time will proclaim my reasons for thus acting. I have forwarded a copy of this letter to the unfortunate lady who is your wife, and I shall forward copies of the letters you wrote my daughter and myself, with full explanations of the whole of the circumstances, to the Bishop of Chichester and to the principal clergy in Brighton.

HENRY WOODHEAD.

Beaumont was obliged to leave the area for a short period after receiving this letter, though he denied the connection.

Stuckey, on behalf of his client said ‘The Defendant, technically speaking, had committed an assault, by taking the law into his own hands, but the reason, having regard for his client and family, he could not divulge. It was evident, by that letter, that something had occurred which had greatly irritated his client…. The assault was of a trivial nature and the justice of the case would be met if the defendant was bound over to keep the peace.’ However, the Magistrate, Mr. Biggs, concluded that no justification for the assault had been given and the defendant was found guilty and fined the sum of £5. The fine was immediately paid, and an assurance given that he would not again molest Dr. Beaumont. Mr Lamb consented, and the case concluded.

Rev. Winham:

A much more positive appraisal is given for the Rev. Daniel Winham. We are told in the Brighton Gazette of 1894 that ‘The Rev. gentleman, who had lived in Brighton for over twenty years, was widely known in the town, and many will receive the news of his demise with the sincerest regret… He was not known so much in public life as in private circles, where his genial and kindly disposition won him a host of friends.

As Christian minister he lived a consistently devout life, and dispensed his means with such a liberal hand that his loss will be most keenly felt by many poor people, several of whom might justly be called his pensioners. He was thoroughly respected and esteemed by all who knew him, and the congregation of St. Andrew's have in their beautiful church, more than one lasting memorial of his devoted labours amongst them… One of the first things he did was to establish a choir school, in which the boys singing in the choir are given a free commercial education, with music and drawing, and assisted in getting an apprenticeship, a recompense for their services in the church.’

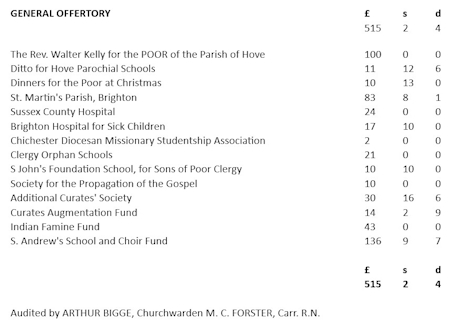

CHARITABLE SERVICES

It would seem useful to remind ourselves of how exactly St. Andrew’s served the Brunswick Town community. What did it offer the local people of Hove?

As mentioned, it had a positive educational input in the local schools as well as its School Choir, which was established in 1869. An inspection of the school in 1877 by R. Blight, Diocesan Inspector, declared that ‘The boys show a very careful and accurate knowledge of Christian teaching, and their intelligence is striking.

It is impossible to overstate the value of this institution.’ In 1882 it was noted that the 14 boys of the school receive, in return for their services, ‘a thoroughly sound Commercial Education, including Music and Drawing and when they leave with a good character, they are assisted in the expenses of their apprenticeship to some trade. Since the establishment of the School 40 boys have been so assisted. They also receive R.E. instruction.’

Some additional contributions to the local society can be seen in the table below.

Information from the St. Andrew’s Church 1929-30 Year Book shows that the church was still thriving, with an organist, choirmaster and many services. It was open daily from 8 a.m. to sunset for prayer and meditation. There were five services on Sunday and regular services on Wednesdays and Fridays.

Of course, as we have mentioned, ceremonies for baptisms, the churching of women, burials and marriages continued to be provided and, as well daily services, there were those for special occasions, such as Advent and Christmas.

Programme of services with Rev. Kirkley

Christmas services with Rev. Evans

Due to the shortage of land in Brunswick Town for burial purposes, burial vaults under St. Andrew’s had been required. The first coffin laid to rest was that of Lord Charles Somerset mentioned earlier. Brighton & Hove Gazette mentions that a medical attendant was present at his funeral, probably his personal physician, Dr. James Barry. (When Dr. Barry died in 1865 it was discovered that this doctor was, in fact, a woman.) A court order in 1854 prevented any further burials in the vaults. But an unusual service was offered in WWII when the vaults were used as air raid shelters.

AN ENDING – OF SORTS

In 1950 St. Andrew’s was made a Grade 1 listed building, a designation used for buildings of an outstanding architectural or historic interest. As time went on, moving into the 1960s the church began to see its congregation dwindle.

In 1962 the church was inspected by John Denman, the well-established local architect. In 1963 yet another appeal was launched for more money. But the church began to suffer from a host of needed repairs, and a general decline in religious attendances. A local newspaper reports ‘The church has had to adapt itself as the district has altered from an estate for the wealthy gentry to a warren of bedsitters and small flats.’

Picture from March 10, 1967, Brighton and Hove Gazette

In 1981 a combined choir of 100 members walked in procession from St. Andrew’s to the Brunswick Lawns, where an open-air service was held, celebrating the 1,300th anniversary of the arrival of Christianity in Sussex.

In 1988/89 a report on the condition of the church was damning and work needed for roofing repairs, gutters, replacement of rotten timber, pipework repair, plasterwork and so on was estimated to be in the region of £35,000 to £45,000. The future of the building as a place of worship was called into question. ‘The basic problem is the one of a dwindling congregation in an already well served with places of worship, with a building no longer in prime condition.’ Also, ‘the difficulty of finding keen young people able to regenerate the congregation and care for the building on a day-to-day basis.’ In 1990 the church closed and in 1991 came under the auspices of the Churches Conservation Trust, one of seven churches they owned in Sussex.

Though no longer a place of worship, it has hosted various events over recent years, for example, a Gay Men’s Choir, art exhibitions and events in the Brighton Festival.

The story of St. Andrew’s Church reflects the area’s changing nature over the years; initially supported by the well-to-do, then receiving less support as the local population becomes less wealthy and less concerned with conventional practices of worship. Whatever its future, it is undoubtedly a building of considerable interest.

Painting – artist unknown (located in St. Andrew’s)

Footnote:

The two artworks which begin and end this document were discovered inside the church, but the artists’ names were not displayed or were indecipherable. Perhaps a fellow researcher is able to enlighten us.

REFERENCES:

1) Brighton Gazette (British Newspaper Archive)

2) Documents at The Keep

3) Hove Civic Society – Brunswick Town

4) Pevsner Archaeological Guides Brighton & Hove

5) Encyclopaedia of Hove & Portslade by Judy Middleton

6) The History of St. Andrew’s Church Waterloo Street by Antony Dale

7) Who Were The Brunswick Commissioners? by Michael Ray

8) www.myantecedents.uk/the-rooper-family

9) Sussex Parish Churches

Research by Shirley Allen, July 2024

Return to Waterloo Street page.