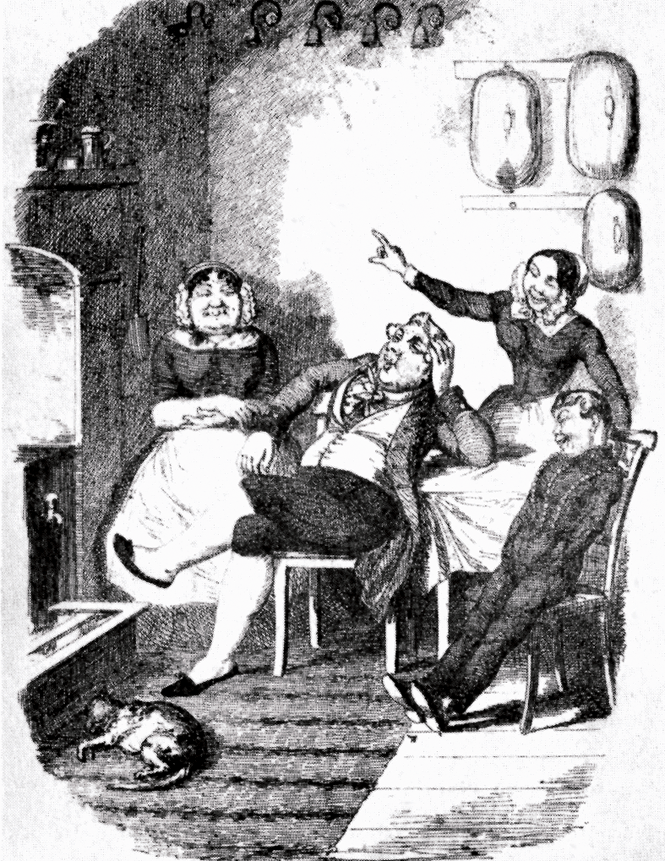

Servants

The smooth running of a Regency household required a large number of servants, so it was fortunate that changing social conditions provided a good supply of applicants. A rising population, changes in farming techniques requiring fewer labourers and the hardships of factory work made life in service an increasingly attractive alternative, especially for men.

In the early nineteenth century labour was cheap and the wages for those in service were among the lowest.

The diary of William Taylor, a footman in a small but well-to-do London household, reveals that in 1837 he was paid 10 guineas per quarter (£42 per annum) supplemented by a further £15 in tips during the year.

In the Royal Pavilion the rather more lowly housemaids were paid a generous £45 per year, well above the national average, so much so that Prince Albert was later to reduce this to a mere £12. Even though £1 in 1820 had the purchasing power of £33.49 in 1999, it still represents an income of only £400 in today's terms.

A typical Brunswick Square family would probably have employed between eight and twelve servants. In spite of the long days and often mundane tasks, domestic service provided a certain amount of security as regular meals and accommodation were part of the package.

Some servants would live in the attic bedrooms and some above the stables, but if these rooms were full then they might have to sleep in the servants' hall and kitchen down in the basement, a vast space laid out for the needs of the working environment that also included some spartan living accommodation.

To the modern eye, the basement is strikingly dark and cold. In the Regency period the only light in these rooms was from the sash windows and tallow candles or oil lamps. These coupled with the small coal fires would have made the basement very smoky.

Original stone flags cover the floors of the basement and the plaster walls have curved corners to allow the servants to move around quickly and easily without injury. The hallway would have been particularly busy with the coming and going of delivery men, bells summoning the maids upstairs and the staff going briskly about their duties.

There was a hierarchy of status and matching delineation of tasks within the household, where the butler, housekeeper and cook or chef formed the ‘senior management’.

The Butler looked after the front door, took messages and calling cards, supervised wine deliveries (and the subsequent re-bottling and decanting as wines and spirits were usually delivered in barrels). He was also responsible for the glasses and silver plate, which would be stored in his room, the ‘butler’s pantry’, for safe keeping. He laid the table and supervised the serving of the food, took the evening tea into the drawing room and finally locked the front door at night.

The housekeeper and cook would take their orders from the mistress of the house and would organise the daily food shopping (essential as perishables could not be kept unless there was access to an ice house) and supervise the general household tasks including mending and laundry supplies.

Other staff included footmen whose special tasks were to clean the boots and shoes, to act as valet to the master of the household, to look after the oil lamps and candles, clean the looking glasses and polish the furniture in the principal rooms and attend the master or mistress when they went out in the carriage.

The delineation of duties was apparent even in the simple task of washing up. For instance, the butler washed glasses (usually in a lead lined sink to help avoid breakages) and also cleaned the silver plate and forks, though knives were the prerogative of the footman. The housemaids washed the china while the washing up of pots and pans fell to the lowly and poorly paid scullery maid.

Most tasks were labour intensive compared with today.

The housemaids rose earliest, to clean the grates and light the fires ready for the family. First the grates and fire irons had to be cleaned by rubbing them with oil and then emery paper or brick dust followed by scouring paper. The rest of the fireplace would be brushed with black lead while the marble hearth would be washed with soap and hot water and finally dried with a linen cloth.

Housemaids would use a tinder box to light the first fire of the day. This contained a flammable fabric such as linen which would be ignited by striking a flint against steel. This in turn was used to ignite a match dipped in sulphur.

Although a servant's life could involve security and companionship, much depended on the employer. William Taylor worked for a kindly and fair employer but nevertheless made these poignant comments in his diary.

The life of a gentleman's servant is something that of a bird shut up in a cage.

The bird is well housed and well fed but is deprived of liberty, and liberty is the dearest and sweetest object of all Englishmen.

Therefore I would rather be like a sparrow or a lark, have less housing and feeding and rather more liberty.

A servant is shut up like a bird in a cage, deprived of the benefit of the air to the very great injury of the constitution.